By Claudio Resta for VT

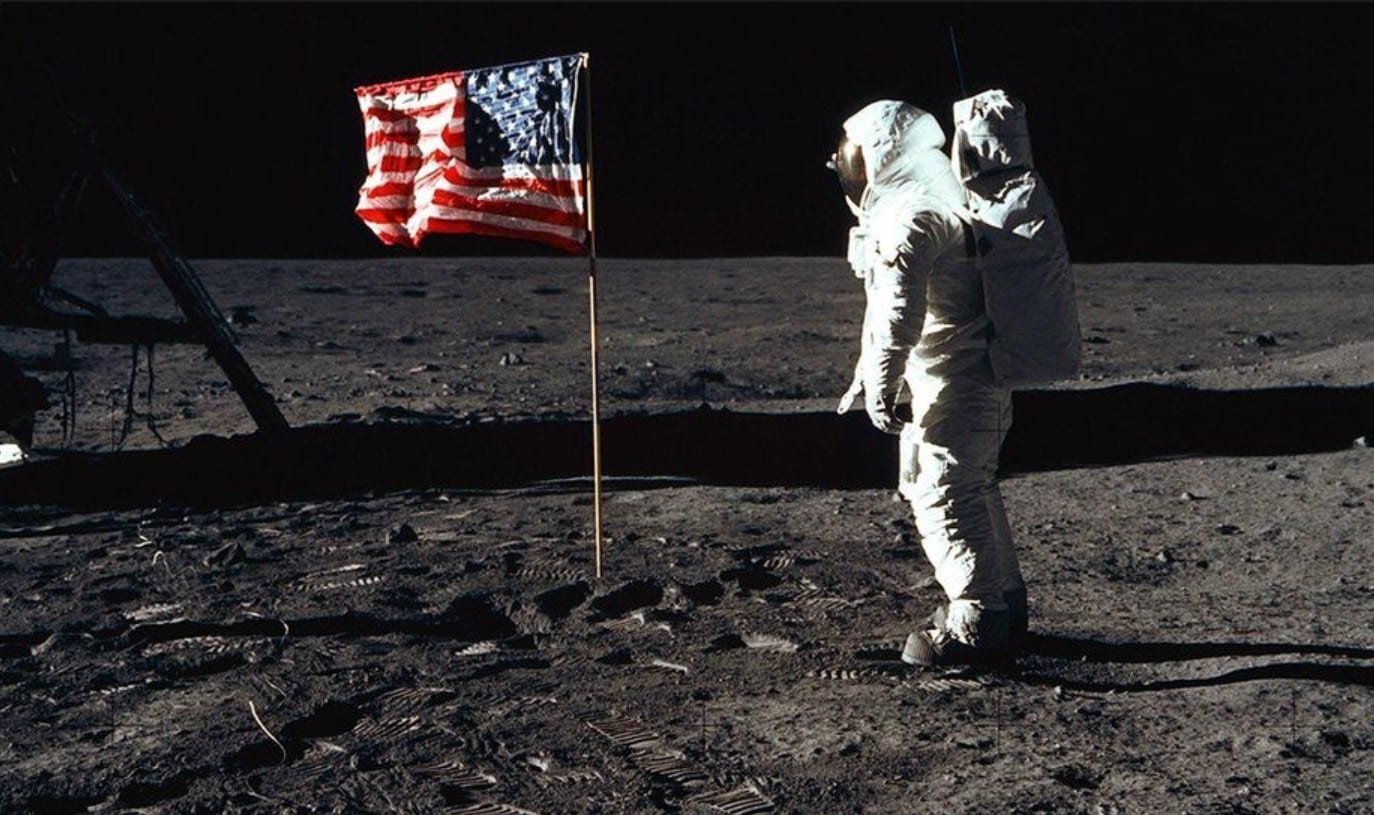

The theoretical background of Psychological Warfare is based on an enduring flow of Fake News made in order to win the Cold War on a symbolic plane: US Moon Landings

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PSYOP), have been known by many other names or terms, including MISO, Psy Ops, political warfare, “Hearts and Minds”, and propaganda.[1] The term is used “to denote any action which is practiced mainly by psychological methods with the aim of evoking a planned psychological reaction in other people”.[2]

Various techniques are used and are aimed at influencing a target audience’s value system, belief system, emotions, motives, reasoning, or behavior. It is used to induce confessions or reinforce attitudes and behaviors favorable to the originator’s objectives, and is sometimes combined with black operations or false flag tactics. It is also used to destroy the morale of enemies through tactics that aim to depress troops’ psychological states.[3][4]

Target audiences can be governments, organizations, groups, and individuals, and is not just limited to soldiers. Civilians of foreign territories can also be targeted by technology and media so as to cause affect in the government of their country.[5]

In Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, Jacques Ellul discusses psychological warfare as a common peace policy practice between nations as a form of indirect aggression. This type of propaganda drains the public opinion of an opposing regime by stripping away its power over public opinion. This form of aggression is hard to defend against because no international court of justice is capable of protecting against psychological aggression since it cannot be legally adjudicated. “Here the propagandists is [sic] dealing with a foreign adversary whose morale he seeks to destroy by psychological means so that the opponent begins to doubt the validity of his beliefs and actions.”[

Fake news, also known as junk news or pseudo-news, is a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media.[1][2] The false information is often caused by reporters paying sources for stories, an unethical practice called checkbook journalism. Digital news has brought back and increased the usage of fake news, or yellow journalism.[3] The news is then often reverberated as misinformation in social media but occasionally finds its way to the mainstream media as well.[4]

Fake news is written and published usually with the intent to mislead in order to damage an agency, entity, or person, and/or gain financially or politically,[5][6][7] often using sensationalist, dishonest, or outright fabricated headlines to increase readership. Similarly, clickbait stories and headlines earn advertising revenue from this activity.[5]

The relevance of fake news has increased in post-truth politics. For media outlets, the ability to attract viewers to their websites is necessary to generate online advertising revenue. Publishing a story with false content that attracts users benefits advertisers and improves ratings. Easy access to online advertisement revenue, increased political polarization, and the popularity of social media, primarily the Facebook News Feed,[1] have all been implicated in the spread of fake news,[5][8] which competes with legitimate news stories. Hostile government actors have also been implicated in generating and propagating fake news, particularly during elections.

In my personal opinion Project, Apollo was conceived by the military-industrial complex in the mid-sixties as a great Psychological Warfare based on Fake News to win the Cold War and enhance the image and prestige of the United States on a political plane and in the meantime to carry on the interest of its economy.

Back to history, President Woodrow Wilson (the 28th president) established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) through Executive Order 2594 on April 13, 1917. The committee consisted of George Creel (chairman) and as ex officio members the Secretaries of: State (Robert Lansing), War (Newton D. Baker), and the Navy (Josephus Daniels).[2] The CPI was the first state bureau to cover propaganda in the history of the United States.

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States created to influence public opinion to support US participation in World War I.

Two key personalities are established around the Committee on Public Information to understand the fundamentals of Psychological Warfare based on Fake News such as the big one culminating to Moon Landings: Walter Lippmann and Edward Bernays.

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974)[2] was an American writer, reporter, and political commentator famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of the Cold War, coining the term “stereotype” in the modern psychological meaning, and critiquing media and democracy in his newspaper column and several books, most notably his 1922 book Public Opinion.[3] Lippmann was also a notable author for the Council on Foreign Relations until he had an affair with the editor Hamilton Fish Armstrong‘s wife, which led to a falling out between the two men. Lippmann also played a notable role in Woodrow Wilson‘s post-World War I board of inquiry, as its research director. His views regarding the role of journalism in a democracy were contrasted with the contemporaneous writings of John Dewey in what has been retrospectively named the Lippmann-Dewey debate.

1919 and was immediately discharged.[18]

Through his connection to House, he became an adviser to Wilson and assisted in the drafting of Wilson’s Fourteen Points speech. He sharply criticized George Creel, whom the President appointed to head wartime propaganda efforts at the Committee on Public Information. While he was prepared to curb his liberal instincts because of the war saying he had “no doctrinaire belief in free speech,” he nonetheless advised Wilson that censorship should “never be entrusted to anyone who is not himself tolerant, nor to anyone who is unacquainted with the long record of folly which is the history of suppression.”

Though a journalist himself, Lippmann did not assume that news and truth are synonymous. For Lippmann, the “function of news is to signalize an event, the function of truth is to bring to light the hidden facts, to set them in relation with each other, and make a picture of reality on which men can act.” A journalist’s version of the truth is subjective and limited to how they construct their reality. The news, therefore, is “imperfectly recorded” and too fragile to bear the charge as “an organ of direct democracy.”

To Lippmann, democratic ideals had deteriorated: voters were largely ignorant about issues and policies and lacked the competence to participate in public life, and cared little for participating in the political process. In Public Opinion (1922), Lippmann noted that modern realities threatened the stability that the government had achieved during the patronage era of the 19th century. He wrote that a “governing class” must rise to face new challenges.

The basic problem of democracy, he wrote, was the accuracy of news and the protection of sources. He argued that distorted information was inherent in the human mind. People make up their minds before they define the facts, while the ideal would be to gather and analyze the facts before reaching conclusions. By seeing first, he argued, it is possible to sanitize polluted information. Lippmann argued that interpretation as stereotypes (a word which he coined in that specific meaning) subjected us to partial truths. Lippmann called the notion of a public competent to direct public affairs a “false ideal.” He compared the political savvy of an average man to a theater-goer walking into a play in the middle of the third act and leaving before the last curtain.

Lippmann was an early and influential commentator on mass culture, notable not for criticizing or rejecting mass culture entirely but for discussing how it could be worked with by a government-licensed “propaganda machine” to keep democracy functioning. In his first book on the subject, Public Opinion (1922), Lippmann said that mass man functioned as a “bewildered herd” who must be governed by “a specialized class whose interests reach beyond the locality.” The élite class of intellectuals and experts was to be a machinery of knowledge to circumvent the primary defect of democracy, the impossible ideal of the “omnicompetent citizen”. This attitude was in line with contemporary capitalism, which was made stronger by greater consumption.

Later, in The Phantom Public (1925), Lippmann recognized that the class of experts were also, in most respects, outsiders to any particular problem, and hence not capable of effective action. Philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952) agreed with Lippmann’s assertions that the modern world was becoming too complex for every citizen to grasp all its aspects, but Dewey, unlike Lippmann, believed that the public (a composite of many “publics” within society) could form a “Great Community” that could become educated about issues, come to judgments and arrive at solutions to societal problems.

Edward Louis Bernays (/bərˈneɪz/; German: [bɛɐ̯ˈnaɪs]; November 22, 1891 − March 9, 1995) was an Austrian-American pioneer in the field of public relations and propaganda, referred to in his obituary as “the father of public relations”.[3] Bernays was named one of the 100 most influential Americans of the 20th century by Life.[4] He was the subject of a full-length biography by Larry Tye called The Father of Spin (1999) and later an award-winning 2002 documentary for the BBC by Adam Curtis called The Century of the Self.

His best-known campaigns include a 1929 effort to promote female smoking by branding cigarettes as feminist “Torches of Freedom” and his work for the United Fruit Company connected with the CIA-orchestrated overthrow of the democratically elected Guatemalan government in 1954. He worked for dozens of major American corporations including Procter & Gamble and General Electric, and for government agencies, politicians, and non-profit organizations.

Of his many books, Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923) and Propaganda (1928) gained special attention as early efforts to define and theorize the field of public relations. Citing works of writers such as Gustave Le Bon, Wilfred Trotter, Walter Lippmann, and his own double uncle Sigmund Freud, he described the masses as irrational and subject to herd instinct—and outlined how skilled practitioners could use crowd psychology and psychoanalysis to control them in desirable ways.[ After the US entered the war, the Committee on Public Information hired Bernays to work for its Bureau of Latin-American Affairs, based in an office in New York. Bernays, along with Lieutenant F. E. Ackerman, focused on building support for war, domestically and abroad, focusing especially on businesses operating in Latin America.[19][20] Bernays referred to this work as “psychological warfareBernays pioneered the public relations industry’s use of psychology and other social sciences to design its public persuasion campaigns: “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it? The recent practice of propaganda has proved that it is possible, at least up to a certain point and within certain limits.”[64] He later called this scientific technique of opinion molding the engineering of consent.

Bernays explained in his 1947 essay “The Engineering of Consent”:

This phrase quite simply means the use of an engineering approach—that is, action based only on a thorough knowledge of the situation and on the application of scientific principles and tried practices to the task of getting people to support ideas and programs.

Bernays expanded on Walter Lippmann‘s concept of stereotype, arguing that predictable elements could be manipulated for mass effects:

But instead of a mind, universal literacy has given [the common man] a rubber stamp, a rubber stamp inked with advertising slogans, with editorials, with published scientific data, with the trivialities of tabloids and the profundities of history, but quite innocent of original thought. Each man’s rubber stamp is the twin of millions of others so that when these millions are exposed to the same stimuli, all receive identical imprints. […]

The amazing readiness with which large masses accept this process is probably accounted for by the fact that no attempt is made to convince them that black is white. Instead, their preconceived hazy ideas that a certain gray is almost black or almost white are brought into sharper focus. Their prejudices, notions, and convictions are used as a starting point, with the result that they are drawn by a thread into passionate adherence to a given mental picture.[66]

Not only psychology but sociology played an important role for the public relations counsel, according to Bernays. The individual is “a cell organized into the social unit. Touch a nerve at a sensitive spot and you get an automatic response from certain specific members of the organism.”

Bernays’ vision was of a utopian society in which individuals’ dangerous libidinal energies, the psychic and emotional energy associated with instinctual biological drives that Bernays viewed as inherently dangerous, could be harnessed and channeled by a corporate elite for economic benefit. Through the use of mass production, big business could fulfill the cravings of what Bernays saw as the inherently irrational and desire-driven masses, simultaneously securing the niche of a mass-production economy (even in peacetime), as well as sating what he considered to be dangerous animal urges that threatened to tear society apart if left unquelled.

Bernays touted the idea that the “masses” are driven by factors outside their conscious understanding, and therefore that their minds can and should be manipulated by the capable few. “Intelligent men must realize that propaganda is the modern instrument by which they can fight for productive ends and help to bring order out of chaos.”

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in a democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. …We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society. …In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons…who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.

Propaganda was portrayed as the only alternative to chaos.

One way Bernays reconciled manipulation with liberalism was his claim that the human masses would inevitably succumb to manipulation—and therefore the good propagandists could compete with the evil, without incurring any marginal moral cost.[71] In his view, “the minority which uses this power is increasingly intelligent, and works more and more on behalf of ideas that are socially constructive.”[72]

Unlike some other early public relations practitioners, Bernays advocated centralization and planning. Marvin Olasky calls his 1945 book Take Your Place at the Peace Table “a clear appeal for a form of mild corporate socialism.” [73]

Bernays also drew on the ideas of the French writer Gustave Le Bon,[74] the originator of crowd psychology, and of Wilfred Trotter, who promoted similar ideas in the anglophone world in his book Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War.[75] Bernays refers to these two names in his writings.[citation needed] Trotter, who was a head and neck surgeon at University College Hospital, London, read Freud’s works, and it was he who introduced Wilfred Bion, whom he lived and worked with, to Freud’s ideas.[citation needed] When Freud fled Vienna for London after the Anschluss, Trotter became his personal physician.[citation needed] Trotter, Wilfred Bion, and Ernest Jones became key members of the Freudian psychoanalysis movement in England.[citation needed] They would develop the field of group dynamics, largely associated with the Tavistock Institute, where many of Freud’s followers worked.[citation needed] Thus ideas of group psychology and psychoanalysis came together in London around World War II.

Vance Oakley Packard (May 22, 1914 – December 12, 1996) was an American journalist and social critic. He was the author of several books, including The Hidden Persuaders, and The Naked Society.

He was a critic of consumerism and a popularizer and in the meantime a critic of theories of Lippman and Bernays that in the fifties were beginning to spread in the field of marketing, PR, Motivational Research, and Advertising and in the political field of propaganda.

In my personal opinion on Wikipedia Source Packard didn’t receive the space he deserves compared to Lippman and Bernays.

Is it for ideological reasons, maybe, since he was attacking the traditional American way of life?

In The Hidden Persuaders, first published in 1957, Packard explored advertisers’ use of consumer motivational research and other psychological techniques, including depth psychology and subliminal tactics, to manipulate expectations and induce the desire for products, particularly in the American postwar era. He identified eight “compelling needs” that advertisers promise products will fulfill.

According to Packard, these needs are so strong that people are compelled to buy products merely to satisfy them. The book also explores the manipulative techniques of promoting politicians to the electorate. Additionally, the book questions the morality of using these techniques.

In a 1964 essay called “The Naked Society”, Packard criticized advertisers’ unfettered use of private information to create marketing schemes. He compared a recent Great Society initiative by then-president Lyndon B. Johnson, the National Data Bank, to the use of information by advertisers and argued for increased data privacy measures to ensure that information did not find its way into the wrong hands. The essay led Congress to create the Special Subcommittee on the Invasion of Privacy and inspired privacy advocates such Neil Gallagher and Sam Ervin to fight Johnson’s flagrant disregard for consumer privacy.

An unheard and undervalued Prophet.

(With many thanks to Wikipedia Source)

Claudio Resta was born in Genoa, Italy in 1958, he is a citizen of the world (Spinoza), a maverick philosopher, an interdisciplinary expert, oh, and an artist, too.

Grew up in a family of scientists where many sciences were represented by philosophy to psychoanalysis, from economics to history, from mathematics to physics, and where these sciences were subject to public display by their subject experts family members, and all those who they were part of could participate in a public family dialogue/debate on these subjects if they so wished. Read Full Bio

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy

An extremely interesting overview article, but with one difficulty of wording: The author follows the Lipmans and Bernaises in using the term ‘democracy/democratic’ about the united partial states of North America. We must keep in mind that the “founding fathers” abhorred the notion of ‘democracy’ of classical antuqity as represented by Athens and San Marino, and much preferred the ‘republic’ as represented by ancient Rome befor the Caesars or Venice ruled by a weak doge under an aristocratic congress chosen by only the founding families. The Roman Republic lasted several hundred years and Venice for more than one thausand years whilst both becoming major empires or hegemones.

So the moon landings were all fake and simply staged in Hollywood?

Comments are closed.