Health Editor’s Note: I had the pleasure of knowing Susan Banyas while going to Chillicothe High School. She and I were on the same cheer leading squad for three years, although she was a year ahead of me in school. Hey, a fun fact about Chillicothe, Ohio; This southern Ohio city was the first and third capital of Ohio. I am pleased to see that Susan used her thespian and literary tendencies to write a socially important play, “The Hillsboro Story“, and is now in the process of writing a book about this important time in civil rights history…..Carol

Meet the Hillsboro Marching Mothers who helped change the course of history

Major, but not well-known, piece of American civil rights movement unfolds in Hillsboro, Ohio

by Alexis Rogers

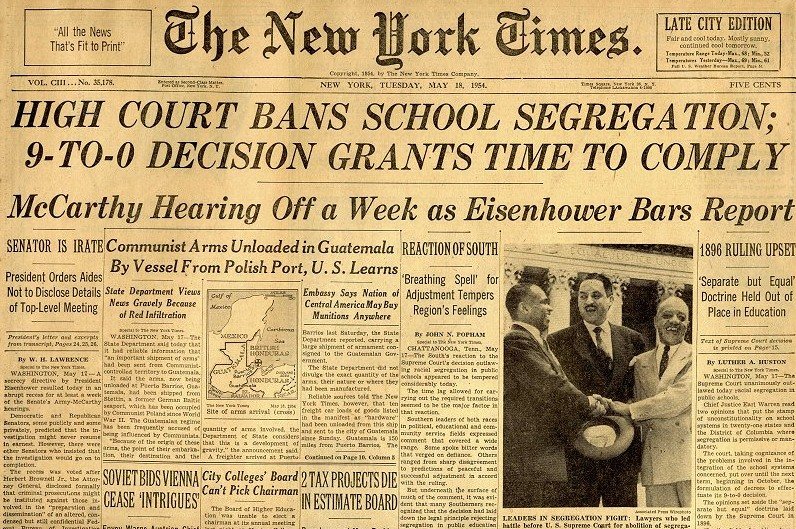

Regardless of the Supreme Court decision mandating the integration of schools in the 1950s, racism was alive and well in Hillsboro, Ohio. It took a group of concerned moms — dubbed the “Marching Mothers” — to get black children in the community the educations to which they were entitled.

THE SCHOOL

If you ask those who were there, like Teresa Williams or Joyce Kitrell, they can tell you that Hillsboro in the 1950s was a reflection of the nation’s deep-rooted disparities.

“You stayed in your place,” Williams said.

Susan Banyas, an activist and playwright, grew up in Hillsboro, just feet away from those like Williams and Kitrell.

“There had been rumblings, you know, but this was very early, before the civil rights movement got going. This is before Dr. (Martin Luther) King (Jr.) stepped up, before the Montgomery bus boycotting,” Banyas said. “I was 8 years old. I was in Mrs. Mallory’s third-grade classroom, and every day outside the window I would see Negro women arriving with their children.”

In 1954, Williams and Kitrell were two of those children outside Banyas’ classroom window. Williams and Kitrell went to the school for black children, the Lincoln School.

“There (were) about 30 kids to one room. The teachers did the best they could with what they had,” Williams said.

“We had never seen a map before. We never really (saw) a good book before. There are two or three subjects that we never before when we went to Lincoln School,’“ Kitrell said.

Hillsboro administrators and town officials refused to integrate the schools, the federal mandate from Brown vs. Board of Education meaning nothing more than a piece of paper to them.

Phillip Partridge, a respected county engineer, didn’t agree.

Carol graduated from Riverside White Cross School of Nursing in Columbus, Ohio and received her diploma as a registered nurse. She attended Bowling Green State University where she received a Bachelor of Arts Degree in History and Literature. She attended the University of Toledo, College of Nursing, and received a Master’s of Nursing Science Degree as an Educator.

She has traveled extensively, is a photographer, and writes on medical issues. Carol has three children RJ, Katherine, and Stephen – one daughter-in-law; Katie – two granddaughters; Isabella Marianna and Zoe Olivia – and one grandson, Alexander Paul. She also shares her life with her husband Gordon Duff, many cats, and two rescues.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy