Article Taken from Bloomberg

Data, documents and interviews show how a focus on cutting prices has come with risks to consumer health.

By Anna Edney/Bloomberg

The day before Donald Trump was elected president, three federal inspectors arrived at Mylan NV’s manufacturing plant in Morgantown, West Virginia, and flashed their credentials. A tipster had raised concerns there might be unscrupulous activity at the factory where the generic giant makes some of its top-selling drugs. So, with Mylan executives looking over their shoulders in a conference room, the inspectors from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, dressed in button-down shirts and ties, began an intense two-week examination.

The team of chemistry experts sifted through thousands of random files containing what appeared to be forbidden exploratory tests, which some drugmakers have used to prevent quality failures from coming to light. The inspectors suspected Mylan laboratory staff had recorded passing scores on drugs that originally fell short of U.S. quality standards.

The files didn’t identify which drugs may have been involved in any exploratory tests. Instead they had obscure names like “lop” and “Medium”—and one that ended in LMFAO, a popular acronym for “Laughing My F**king Ass Off.”

The inspectors also found bins full of shredded documents, including quality-control records, in parts of the factory where every piece of paper is supposed to be saved. The list of alleged infractions became so long that a fourth inspector was added. A warning letter, the FDA’s strongest rebuke, was drafted. It would mean the agency could refuse to consider any Mylan application for a new drug made at that plant until the company fixed things.

But the warning letter was never sent. Eight months later in July 2017, higher ups at the FDA apparently decided to take it easy on Mylan, the second-largest generic drugmaker, with $12 billion in revenue in 2017. The FDA ultimately left it in the company’s hands, and the drugmaker promised to address what the agency calls a “data integrity” issue.

The FDA didn’t say specifically why it chose not to warn the company. “The FDA issues warning letters when it deems it necessary to take such action based on a combination of factors, including FDA inspectional findings, follow-up with companies and other factors,” said Sarah Peddicord, an agency spokeswoman. Mylan said it demonstrated to the FDA that the testing in question “occurred in the development environment and was not associated with commercial product.”

When Scott Gottlieb became FDA commissioner in May 2017, he made getting more generics to market a top priority so the extra competition would drive down drug prices, something President Trump had pledged to do.

Gottlieb’s actions on generic approvals have drawn praise from both parties in Congress, which is holding hearings on drug prices Tuesday. But with Democrats having taken control of the House, members who oversee the FDA say they plan to examine a crucial public-health question posed by his efforts: Is the fast-tracking of those approvals coming at the expense of oversight that’s supposed to ensure that drugs already on the market are safe and effective?

In a year-long investigation into FDA’s regulation of the generic-drug industry, Bloomberg examined hundreds of pages of inspection documents; reviewed more than 10 years of inspection data and thousands of pages of pretrial depositions; and interviewed more than two dozen current and former FDA inspectors and agency officials, lawmakers, and industry experts.

Concerns about quality control and data integrity have focused on numerous companies in India and China, where more and more drugs and active ingredients used in medicine for the U.S. are being made. But the interviews and documents suggest that those concerns aren’t limited to overseas factories. And the issues surrounding them are twofold: a drop-off in inspections in many places and, in some cases, the softening of penalties when problems are found.

Failures of quality control have also become a matter of dispute between generic-drug companies. Last month, the Delaware Supreme Courtpermitted the German company Fresenius SE to back out of its $4.3 billion takeover of Lake Forest, Illinois-based Akorn Inc. after Fresenius learned of a longstanding pattern of such problems in Akorn’s drug development and manufacturing systems.

In a taped deposition for the case, a pharmaceutical consultant testifying for Akorn said its issues are commonplace. “It is not unique to any one company,” said George Toscano, a data integrity expert at consulting firm NSF International who has done hundreds of drug-manufacturing audits. “It’s something that the entire industry is struggling with.”

In the face of such problems, the FDA approved a record 971 generic drugs in the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, according to a report from the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. That was a 94 percent increase over fiscal 2014, when 500 were approved.

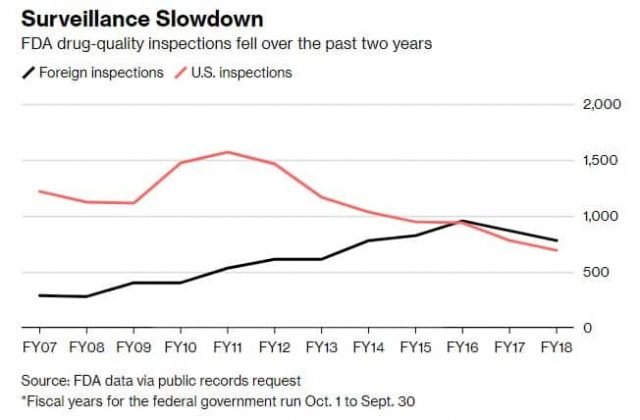

Yet the number of so-called surveillance inspections done globally by the FDA—meant to ensure existing drug-making plants meet U.S. standards—dropped 11 percent, to 1,471, in fiscal 2018 from fiscal 2017. Those inspection numbers also decreased in fiscal 2017, which included Gottlieb’s first few months in office, falling 13 percent from the prior year. The figures were obtained through a public-records request.

Surveillance inspections of just U.S. drug factories declined 11 percent, to 693, from fiscal 2017 to fiscal 2018, the lowest going back for at least a decade, the data show. Such inspections have been falling since 2011, as the agency began focusing more on foreign manufacturers.

Meanwhile, from fiscal 2017 to fiscal 2018, surveillance inspections of foreign factories fell 10 percent, to 778. This was the second year-over-year decline, after surveillance inspections of foreign factories dropped 9 percent from fiscal 2016 to fiscal 2017, reversing a trend of rising inspections over most of the previous decade. One marked exception to the recent drops: India, where inspections jumped 18 percent in fiscal 2018.

While inspections alone don’t ensure the safety of America’s drug supply, they are one of the few concrete measures available to assess FDA’s oversight. Even among agency veterans, there is strong disagreement over what the recent declines in inspections means.

Gottlieb and others say it reflects a smarter, more surgical approach. “It’s not the number of inspections we do, it’s whether we’re targeting effectively,” he said.

Industry proponents and the FDA say it decides which facilities to inspect using a risk score calculated by the agency. They also say that the FDA can’t inspect its way to better quality drugs, particularly with the limited resources it’s given, and that it’s up to drugmakers to police themselves.

But others, including Margaret Hamburg, the FDA commissioner under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2015, see cause for concern, given the sprawling complexity of the system delivering more and more of the drugs that Americans consume. “Maintaining, if not increasing, inspections would seem crucial, given the global sourcing, supply chain, increase in approvals and quality issues,” Hamburg said after Bloomberg shared the inspection numbers with her.

Lawmakers shown the figures expressed similar worries—that the recent figures could reflect the agency putting approvals above enforcement. This was particularly true in the case of China, where FDA inspections fell almost 11 percent even as U.S. regulators oversaw a massive recall of a Chinese-made heart drug contaminated with a possible cancer-causing chemical.

“Any actions by the FDA to prioritize expediting drug approvals over ensuring manufacturing quality and compliance would be concerning, as it has the potential to risk patient safety,” said Representative Frank Pallone, the New Jersey Democrat who is the new chairman of the House Energy & Commerce Committee, with jurisdiction over the FDA. “I look forward to hearing more from the agency about how they are balancing both missions.”

To patients in the U.S., the origin of their drugs shouldn’t make a difference. Whether treatments are made in West Virginia or Mumbai, they’re supposed to meet FDA standards for safety and efficacy. But as the industry has become increasingly global and desire for lower drug prices continues to grow, signs are indicating that U.S.-made drugs aren’t immune from the same forces that have led to corner-cutting overseas.

The FDA’s current approach was mandated by a 2012 law. To determine when to visit a facility, the agency takes into account when the facility was last inspected, what that most recent look found and what the plant manufactures, among other factors. The agency sends inspectors to facilities with the highest risk scores first.

“There’s things that go wrong that are hard to predict,” Gottlieb said. “But there’s certain actors that are more likely to make mistakes that present public-health challenges. And there are certain actors that are more likely to do something deliberate—and those are the ones that you need to be focused on.”

Congress focused on drugmaker inspections after a 2008 crisis in which a contaminated blood thinner called heparin made in China was linked to more than 200 deaths in the U.S. Lawmakers used the 2012 law to boost the FDA’s ability to inspect foreign drugmakers.

Today, 90 percent of the medications that Americans take are generics. They’re cheap because they rely on research done by brand-name pharmaceutical companies. When a brand-name drug’s patent protection runs out—generally after about 20 years—a generic firm can copy the product. The maker only has to prove it works the same as the original, saving hundreds of millions of dollars on research and development.

Those savings are typically passed on to the patient who, after several generic versions of a single drug hit the market, will pay up to 80 percent less. The more generics competing against each other to sell a single drug, the lower the price; hence Gottlieb’s push to get more of the copycat drugs to market.

Prices remains a key interest of the Trump administration, and in recent weeks Congress has introduced several bills to contain them.

Carol graduated from Riverside White Cross School of Nursing in Columbus, Ohio and received her diploma as a registered nurse. She attended Bowling Green State University where she received a Bachelor of Arts Degree in History and Literature. She attended the University of Toledo, College of Nursing, and received a Master’s of Nursing Science Degree as an Educator.

She has traveled extensively, is a photographer, and writes on medical issues. Carol has three children RJ, Katherine, and Stephen – one daughter-in-law; Katie – two granddaughters; Isabella Marianna and Zoe Olivia – and one grandson, Alexander Paul. She also shares her life with her husband Gordon Duff, many cats, and two rescues.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy