… by Jim W. Dean, VT Editor

[ Update Editor’s Note: I went way back into the archives for this one, April 3rd 2011. Gordon had given me a blank check when I came aboard VT to experiment with magazine style templates. I typically did these on weekends when I had more time. The VT pace was slower by then, as we had most of the staff writers self posting.

This should be enjoyed with a cold beer or a good glass of wine. I would save Zeamer’s video until after you have gone through all of the rest. It will mean more to you if you do.

Jay Zeamer has been dead for a while, but I did a google on him anyway to see if anything new had been found and posted, and bingo… I found this 7.5 minute interview, so here it is in my intro.

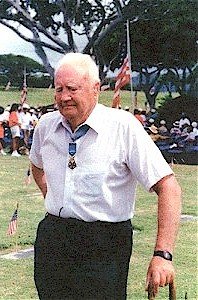

I also found the photo of his getting his MoH. It took a miracle for Zeamer not to get this posthumously, but then again there would have been no witnesses with the plane going down, so the story would have been a missing in action one.

But it also took the fantastic skill he had as a pilot with a plane full of washed out discipline problems, something you would think was a Hollywood fiction script, but was the real deal. We salute all the unknown who died doing similar things that were just not seen and we will never know.

Woody Williams told me in his interviews right here in this room that Medals of Honor were being earned on Iwo Jima everywhere you looked, but the witnesses often were dead within a day or two. That is why the code of the Medal of Honor Society is that they wear the award for all those that did not get it, but who deserved to… a first class act.

Marine general Vandegrift, who got his for Guadalcanal, took a different view, telling the 13 Marines (individually) who got theirs with Woody, “That medal does not belong to you. It belongs to all those that did not come back, so don’t you ever do anything to tarnish it,” some tough love from the general.

Jay Zeamer had a good life. He was already an MIT ROTC civil engineer when he went to war, and became an aeronautical one after he got back, and could afford to raise four daughters.

I have a hand-written letter from him to the daughter of his radio operator, sent when he had died, explaining how he had kept Zeamer alive during the long flight back and figured a way to use radio navigation to find their base, or they just would have gone down in the ocean out of fuel.

I built this piece from the “Old 666” video, and then dug up the years of work that the nephew of KIA MoH Lt. Sarnoski had spent researching, including going to Japan to dig through their archives. It really filled the story out past what was in the original video.

And this taught me that VT could really be different if we had the time to try harder, dig deeper, to find what those before us had missed. We are known for this, with our historic Intel consulting work we are sometimes called on to do, the “what really happened with, in such and such”, something that Gordon knows more than anyone else that we know due to access that he had and his photographic memory.

We have tried to share as much as we could with you, because we also felt we had a duty to those who did not come back; one we have served in our own way. Being with VT has privileged me to enjoy these experiences that I never would have had otherwise, making me also a lucky man who has had his life enriched by those passing through it.

Jay Zeamer knew that his Medal of Honor belonged to the whole crew, and he never let them forget that. We should all be so lucky to have such a crew, or pilot, or a bombardier like Joe Sarnoski. And we should all try to be worthy of the honor… JD – 2016 ]

____________

VETERANS TODAY EXCLUSIVE: Combat – The Greatest Air Battle of WWII (4 videos)

By Jim W. Dean STAFF WRITER/Editor

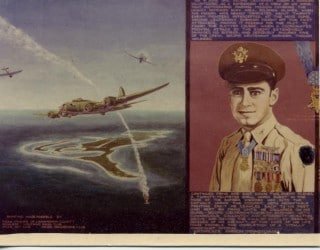

In the video below you will hear about Capt. Jay Zeamer in his B-17 bomber ‘Old 666’ and ‘Eager Beaver’ crew fight a running 45 minute air battle with over two dozen Japanese fighters from Buka and Bouganville airbases. They were frantically trying to end their critical mapping flight for the future Bouganville Marine landings.

Zeamer and his nose gunner Lt. Joe Sarnoski were awarded Medals of Honor, the latter’s being posthumous. The rest of the crew received the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor. I am 61, and this is the most amazing air combat story that I have read.

Five Japanese planes were shot down, three in the beginning of the fight while making dueling head on passes. These surprising early losses saved the day as the other Japanese fighters were gun shy after that.

Although severely wounded Sarnoski crawled back to his twin 50’s in the completely shot out nose bubble and continued firing until he collapsed from loss of blood.

Zeamer fought the battle with a 100 pieces of shrapnel and a broken leg, his cockpit controls shot to pieces, and did not relinquish command to his co-pilot until the fighters broke off when their fuel was running low

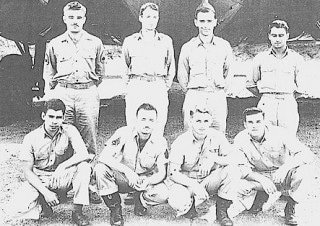

Zeamer and his crew of Eager Beavers already had earned a slew of combat medals before the this battle. Before getting to fly together, all had been ‘discipline problems’ and had been on the bottom of the flight list.

Zeamer had consistently failed to check out as a pilot and was only flying the old 666 because he and his crew had salvaged it from the parts dump.

Walt Krell recalled, “He (Zeamer) went through the outfit and recruited a crew from a bunch of renegades and screwoffs. They were the worst of the 43rd–men nobody else wanted. But they gravitated toward one another and they made a hell of a crew.”

But this is a double barreled piece today. The video is actually a lead off to an archival description of this battle. I had initially thought this would be a quick story with a lead in and the video which at ten minutes would usually be enough. But this blew my mind to the extent I went digging for more and hit the jackpot.

I found a history teacher, Jim Rembisz, who just happened to be Joe Sarnoski’s nephew. He spent years digging out the archival record, including the Japanese reports which give you a rare second view of a battle like this. This is a keeper, folks. Please pass it around. It was a pleasure to do for you.

And as often was the case with so many WWII veterans, and even the heroes, Zeamer’s daughters never knew he had won the Medal of Honor until they were adults. My own father (P-40, P-51 pilot) only had one war conversion with me when I was 22. It required the seduction of a huge grilled T-bone steak plus splitting a bottle of bourbon with him.

___________

The Eager Beaver crew story continues now with Jim Rembisz’ archival material…

To make matters even more comical, Jay’s misfit crew didn’t have an airplane. There again, Zeamer had his own ideas. One day an old B-17E with the tail number 41-2666 was flown in and parked on the airstrip.

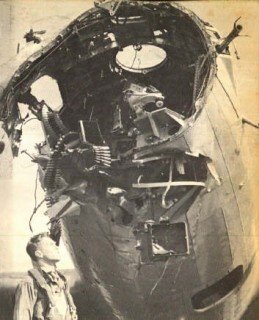

The bomber had seen better days and its frame bore evidence of its heavy record of aerial combat. It was so badly shot up it was now worthless, and was parked at the end of the runway where other aircrews could cannibalize it for needed parts. Captain Zeamer quickly intervened and claimed it as his own.

Zeamer’s crew went to work on what would normally have been an impossible task–turning #41-2666 into a combat-ready bomber. They cleaned it up, patched the holes, fixed its engines, and modified it to their liking.

Jay had a 50-caliber machine gun mounted in the nose so he could fire from the cockpit like a fighter pilot. In the nose, the 30-caliber flexible guns normally manned by the bombardier and navigator were replaced with swivel-mounted 50-caliber machine guns. The waist guns and radioman’s guns were replaced with twin-50s, giving the airship unprecedented firepower.

Zeamer’s crew put guns where they didn’t even need guns, leaving loose machine guns on the catwalk so that if a gun jammed at a critical moment they could dump it and quickly replace it with a spare. Sergeant George Kendrick even mounted a gun behind the ball turret near the waist. “I don’t know who would have handled that except the side gunner” Jay recalls.

“He wanted all the guns he could get! He wouldn’t let another gunner back there with him. He said, ‘These are my guns. I’m going to shoot them all. I don’t want to be bumping asses with another guy back here!’ This was George Kendrick, the screwball of the crew.”

In truth, in the eyes of the other pilots and ground crews at Port Moresby, the entire crew was screwballs. That impression aside however, it quickly became apparent that the men were building a flyable, fightable, bomber.

At a time when aircraft and spare parts were in short supply, quickly other pilots and ground crews began eyeing #41-2666 enviously.

Walt Krell recalled what happened when it came to a head. “Jay was so mad…he ordered his men not to give up the airplane and they weren’t about to see that happen. By now they would have done anything for Zeamer. They loaded their fifty calibers and they told everyone to stay the hell away, and Zeamer and his crew even slept in that damn airplane for fear someone would try to take it away from them…Everyone was talking about him and his renegades.”

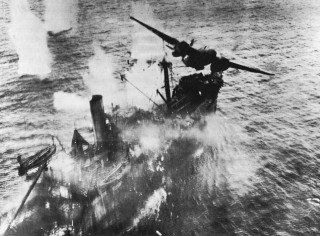

In the meantime the Fifth Air Force continued its regular run of bombing missions against the Japanese, and many of these were flown by Captain Jay Zeamer and his Eager Beavers. In May Zeamer and crew made a skip-bombing run on a Japanese aircraft carrier, swooping within fifty feet of its decks.

A few days later on a daylight bombing raid over Rabaul, Old 666 came in so low it was brushing the roofs of the housetops. It seemed that the Eager Beavers were fearless. Everyone in the 43rd Bombardment Group was talking about them, and now in some very respectful tones.

“Whenever the 43rd got a real lousy mission–the worst possible mission of all that nobody else wanted to fly–they went down to see Jay Zeamer and his gang,” said Walt Krell. “They couldn’t keep them on the ground, no matter how bad or rough that mission might be. They didn’t care.

They crawled into that airplane and just flew and what was more they always carried out their missions. It was the damnedest thing. They’d fly in the worst possible weather, the kind of storm that madeother pilots grateful they were on the ground.

“Zeamer would always find his way in. Sometimes the weather would be so bad, in ships that were shot up, other planes would crash, or the crews would bail out because it was impossible to get back down safely. Impossible for everyone except Jay Zeamer, that is.”

One of Zeamer’s missions over Rabaul was a psy-ops flight during which pamphlets were to be dropped. Approaching the enemy stronghold Zeamer told his crew, “Don’t throw them out. I’ll go down low enough so you can pass them out individually, but no lally-gagging around those geisha girls.”

On a night mission over Wewak the Japanese gunners on the ground managed to fix the flight of incoming American bombers in the glare of several large search lights. Zeamer got mad and made good use of his specially designed nose gun.

In an incredible display of courage and airmanship he dove on the positions, shooting out three of them and damaging two others. His actions enabled the squadron to complete its mission and get back safely. That action earned the renegade pilot an oak leaf cluster to his Silver Star.

Zeamer’s daring and skill gave his crew great confidence. They believed they could fly anywhere, accomplish any mission. They were convinced that no matter what their condition, Captain Zeamer would always get them home.

On a May 5 mission over Madang Old 666 was hit more than sixty times by anti-aircraft fire, the stabilizer was shot out and the oxygen tanks exploded. Validating his crew’s confidence, Zeamer somehow managed to get everyone back safely despite the extreme combat damage. Soon the Flying Fortress was patched up and ready to fly its next mission.

Captain Zeamer was equally loyal to his crew. All of them had been decorated again and again for their heroics. Both Sergeants Vaughn and Pugh had been awarded Silver Stars, and Sergeants Able and Kendrick had each been awarded the Silver Star and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Master Sergeant Joseph Sarnoski had been awarded the Silver Star and Air Medal, but in Sarnoski’s case it wasn’t enough to satisfy Jay Zeamer. He was instrumental in seeking promotion for his enlisted bombardier and, thanks to Jay’s efforts, on May 24 Joe Sarnoski became a second lieutenant.

It was, recalled Walt Krell: “a reconnaissance mission that nobody wanted to take. Nobody in his right mind, maybe. So they went to see Jay Zeamer and his crew.” “That job had been hanging for months, and nobody else had been able to do it,” Captain Zeamer wrote in a letter five months after the mission.

“We just put extra guns all over our ship hoping to be able to fight our way clear. We had 19 machine guns which is more than any other Flying Fortress in the Southwest Pacific has ever thought of having.”

Eager Beaver bombardier Joe Sarnoski could have…indeed by all standards SHOULD have…been excused from the mission. The young 2nd lieutenant had spent nearly 18 months in the combat theater and had flown dozens of missions and earned both the Silver Star and Air Medal.

More recently he had been ordered home to instruct new bombardier recruits. His bags were all packed; his departure was to be effective three days hence–June 19.

By the time darkness fell over Port Moresby on June 15 Old 666 was armed to the teeth and ready for action. While the crew headed for their cots to get a good night’s rest before their 4 a.m. takeoff, Captain Zeamer was given an additional last-minute order.

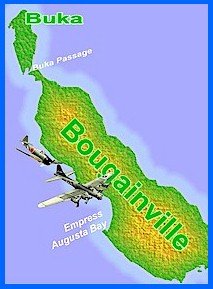

While in the air over the coastline of Bougainville, he was instructed to fly over the smaller island of Buka which was separated by a thin waterway known as the Buka Passage. There he was to make a reconnaissance of the Japanese airfield there to determine logistics and enemy strength.

This new assignment changed the mission from being one of immense danger to one of sheer suicide. Captain Zeamer was furious. His mission was to photograph Bougainville and then get the images back home.

A side trip over Buka would almost surely doom his airplane and crew, making the entire mission a futile waste. As he turned in for the night Zeamer had already made up his mind that he would photograph Bougainville, but he would not risk his men or his B-17 over Buka.

For three hours Old 666’s four, big engines churned the air as Jay Zeamer flew into the rising sun and one of Japan’s most fortified islands. Shortly before 0700 the faint dawn revealed the distant outline of Bougainville Island.

The B-17 was thirty minutes ahead of schedule. The sun had not yet risen high enough to illuminate the island’s west coast sufficiently for photographic purposes.

“Aw, hell….” Zeamer thought as he considered his early arrival and pondered the suicidal last-minute order he had previously determined to ignore. “Navigator, plot a course for Buka,” he announced.

Minutes later a thin slip of water passed 25,000 feet below the Fortress, and then the dense jungle of Buka appeared in the lens of Kendrick’s camera.

Carved in the foliage below was a honeycomb of small airplane revetments, all leading to a massive airstrip. With a sinking feeling Captain Zeamer suddenly realized why headquarters wanted this recon–more than 400 enemy fighters had been flown into the Buka aerodrome the previous day.

In the belly of Old 666 Sergeant Kendrick snapped a photograph while noting the time in his camera log. It was 0700. Later that photograph would reveal twenty-one enemy fighters either warming up or taking off to interdict the American bomber.

“The thing we should have done then was high-tail it for home,” Zeamer later stated. But even as Sergeant Forrest Dillman announced over the interphone from behind his guns in the ball turret that he could see enemy fighters taking off, Captain Zeamer turned southeast to level off and begin his photo/mapping mission of Bougainville’s west coast.

“The mapping had to be done that day,” Zeamer explained years later. With the invasion of Bougainville already being planned, those photographs would mean life or death to thousands of young American Marines.

“They had to know where the coral reefs were. A landing craft getting caught in a coral reef would result in the men getting blown out of the water before they could get overboard. So it was most important for us to get the photographs from which charts could be made.”

Prop-wash kicked up a cloud of dust on the earthen runway at Buka as Chief Flight Petty Officer Yoshio Ooki throttled the engine of his A6MZero. In the distance the American Flying Fortress that had dared to make a lone incursion over Buka was fading slowly, to become little more than a speck in the clear dawn of the morning.

Ooki gave a thumbs-up and then his fighter was taxiing for takeoff. Behind him roared the engines of seven additional Zeroes, the remainder of the Japanese commander’s battle-tested squadron.

The 251st Kokutai was part of the recently arrived reinforcement of 400 aircraft at Buka, following distinguished service nearer the Japanese home islands.

The cracker-jack outfit was part of the massive air power shift to the Solomons in the Empire’s desperate attempt to turn back the sweeping air superiority gained by General Kenney’s 5th Air Force.

Ooki’s pilots were veterans, skilled fighters, and able tacticians who were determined to surprise the American pilots with their aerial prowess.

On this day Yoshio Ooki had no doubt that if he and his men could catch up to the fading B-17, they would send it down in flames.

It was slow work, climbing for altitude and racing to catch the enemy bomber, but Ooki and his squadron nursed every ounce of speed out of their engines.

The race was too much for Shunichi Yahiro’s fighter, and while still in pursuit the Japanese pilot’s engine gave out and sent him crashing into the sea. Yahiro survived and was later rescued, but at that moment Ooki’s only thought was for the B-17 in the distance.

The American Flying Fortresses were known to be heavily armed and had successfully fought off five, six, and occasionally even more fighters. But the numbers today were certainly against the Americans.

To increase the odds, Ooki’s remaining seven Zeroes were joined in the air by at least two twin-engine Dinah’s. Ooki knew also that the other airfields on Bougainville would quickly field more Zeroes, should they be needed.

The morning sun was creeping over the island and bringing with it a light cloud cover, but as he raced southward Ooki couldn’t believe his luck. The pilot of the American bomber was making it too easy.

The big airplane didn’t break and run for the clouds–didn’t dive and head out to sea. Instead, the pilot continued on a straight and level heading. It was as if the enemy pilot was begging to be attacked and destroyed.

Captain Zeamer was indeed making it easy for the enemy fighters. “The mapping had to be extremely accurate and you don’t dare dip the wing a degree or the focal point on the ground moves over a mile,” he recalled in one interview. At 0740 Zeamer had only 22 minutes of flight-time remaining to complete his mission.

In the distance the crew could make out the shapes of at least fifteen Zeroes and two Dinahs. No one would have faulted the crew had they then opted to turn and run for home. Zeamer’s Eager Beavers knew, however, that for the first time in months the important photos of Bougainville were being recorded on film. These were pictures that could save thousands of American lives.

In the belly of Old 666 Sergeant Kendrick kept his camera rolling. In the clear Plexiglas nose Lieutenant Sarnoski stood ready at his guns, scanning the sky ahead for any sign of enemy fighters that might try to attack from the front.

In the cockpit Captain Zeamer held his course while the co-pilot and navigator called out numbers, helping him to keep the wings level, the air speed constant, and the bomber’s altitude consistent at 25,000 feet.

In the distance Jay could make out the wide opening at the middle of the Bougainville Island. That would be Empress Augusta Bay, he knew.

If he and his crew could hold on for just another twenty minutes their mapping mission would be completed. The respite bought by the aggressive and accurate fire of Pugh and Dillman might prove to be just enough.

The hail of 50-caliber machine gun fire that swept past Yoshio Ooki’s canopy did little to dissuade his determined assault on the lone Flying Fortress. Leading his squadron into the battle, Ooki winged over to sweep wide around the bomber.

The American pilot gave no indication of diverting from his suicidal course, so the Japanese squadron chose to take advantage of the situation by getting in front of him and attacking the bomber’s most vulnerable position–the nose.

The maneuver took more than fifteen minutes, the Zeroes speeding off to the side and then circling to get in front of the B-17.

By the time the Fortress was over Empress Augusta Bay, Ooki and five of his fighters were well in front and turning for an all-out attack on the nose and cockpit.

Ooki’s seasoned pilots were spread out neatly from left to right in the 8 o’clock, 10 o’clock, 12 o’clock, 2 o’clock and 4 o’clock positions. It was a semi-circle of certain death.

When Ooki gave the command to attack, all five Zeroes would come in with 20mm cannon and 7.7mm machine guns firing.

The two opposing forces were on a collision course at a combined speed of more than five hundred miles per hour. Still the pilot of the American bomber stayed straight and level–almost as if oblivious to the presence of impending doom.

Captain Zeamer was far from oblivious of the enemy presence, however. He knew he was in trouble, and worse, he knew he was up against a formidable foe.

In nearly a year of combat that included 47 aerial missions, Captain Zeamer had never seen more than two Japanese fighters in a coordinated frontal attack.

Such tactics required timing, practice and precision. Now he faced FIVE fighters in such an arrangement. Jay knew these enemy pilots were good–VERY GOOD!

As Ooki’s squadron dove in with guns blistering the sky Zeamer was less than minute from completing his mission. He also knew the enemy would be on top of him in far less time than that.

“The dumbest thing you can do with a B-17, when you’re under attack against fighters, is to hold it straight and level,” Jay recalled. “Everyone I know who did that (against two fighters) got shot down. But here are five coming in five different directions. I thought, ‘My gosh, if I maneuver against one, I’ll make myself better game to the others.’ That, coupled with the fact that the mapping was important, I kept going straight.”

The two forces met over Empress Augusta Bay at 0800. Yoshio Ooki dove his Zero towards the cockpit of the American bomber and unleashed his 20mm cannon. Breaking off less than 50 feet from the point of collision, the two pilots might well have seen the surprise, each on the face of each other.

While holding his bomber on course, Zeamer had unleashed a string of 50-caliber rounds from his own specially mounted nose gun, raking Ooki’s Zero and sending him plummeting earthward with fuel streaming from his wing tanks.

Old 666 shook with the force of fire from all its nose guns, then trembled as Ooki’s 20mm destroyed the cockpit. Simultaneously, Lieutenant Sarnoski fired at the Zero to the left (at the 10 o’clock position.) It erupted in front of the nose from the bombardier’s accurate fire, but not before one of its own 20mm canon shattered the Plexiglas of the American bomber.

Sarnoski was thrown backward, beneath the catwalk. His body was shredded with shrapnel and broken glass. A deadly gash in his side had nearly split him in half.

In the cockpit Captain Zeamer could see what was happening below. The enemy cannon had ripped huge holes in the floor of the cockpit and peppered the his own legs and feet with small pieces of shrapnel.

Air screamed in through the holes in the floor, and Zeamer watched as Lieutenant Johnston rush to the mortally wounded bombardier to try to stem the flow of blood from a neck wound.

Joe Sarnoski shook him off. “I’m alright,” he struggled to announce. “Don’t worry about me.” More enemy fighters were now firing on the bomber’s shattered nose, and every gun was needed in those critical moments.

Slowly, painfully, Joe Sarnoski dragged his body across a torn catwalk that was now slick with his own blood. He forced himself upright and from a crouch opened fire on a twin-engine Dinah that was moving in for the kill.

Once again Sarnoski’s accurate fire sent an enemy fighter down in flames, but not before more cannon fire hit the cockpit.

More than 100 pieces of sharp metal from this new fusillade tore into Captain Zeamer, shattering his feet and paralyzing his legs. Bullets sprayed the cockpit and tore into the pilot’s arms and legs.

“I never felt so much pain in my life,” he recalled. “One of the shells exploded at my feet. It ripped off my rudder pedals, tore gobs of flesh from my legs, and shattered my left knee. Blood from my ruptured wrist was spurting across my lap every time my heart pumped.”

Captain Zeamer and his crew had run out of time. The last explosion had ruptured the bomber’s hydraulic system, destroyed the cockpit flight instruments, and severed control cables.

It had also knocked out the oxygen supply and, at 25,000 feet the crew would quickly be rendered unconscious unless Zeamerdove. Despite his agonizing pain, he found the strength manipulate the controls and bank hard to the right, plummeting to 10,000 feet above the sea.

Falling behind Jay Zeamers bomber in his own desperate effort to avoid disaster, Yoshio Ooki fought his own controls to nurse his fighter back to Buka. Pilot Hiroshi Iwano protectively followed his squadron leader in his own undamaged Zero.

Three pilots of the 251 Air Squadron had also taken hits from the accurate fire of Zeamer’s besieged bomber (Tadaharu Sakagami, Tadashi Yoneda, and Ichirobei Yamazaki), but Kooichi Terada apparently never got in position to fire a round.

The eighth Japanese fighter, piloted by Suehiro Yamamoto, had to break off and return home after expending all of his ammunition.

In all, 251 Squadron reported firing more than five hundred 20mm and more than seven hundred 7.7mm rounds in their attempt to destroy the Flying Fortress that had dared to venture alone into the heavily defended Bougainville/Buka area.

It was small comfort for the crack Nippon squadron that had lost one fighter in the ocean and suffered four others badly damaged.

Contrary to Yamamoto’s report, Old 666 did not crash into the mountains. Captain Zeamer struggled with the controls to pull his bomber out of its dive and level off at 10,000 feet.

Then he pointed her shattered nose westward, towards home 600 miles distant. Fighting off waves of pain Jay struggled to keep his bomber in the air.

Meanwhile at least seventeen enemy fighters from other enemy squadrons dove downward on the withdrawing Flying Fortress to deliver the coup de grace. Sergeant Able flamed one of them with the twin-50s in the top turret but paid for it in pain. Enemy rounds struck him in both legs.

Time and again enemy fighters tried to race ahead of Old 666 for another frontal attack. The nose guns were out of commission from the heavy damage, Lieutenant Johnston was now wounded, and Lieutenant Sarnoski was slumped silently over his own machinegun.

He had mercifully slipped into unconsciousness after summoning one last effort of unbelievable strength to turn back the final deadly assault.

Fortunately, with the mapping mission done, Captain Zeamer was now able concentrate on maximum airspeed and evasion. “I just maneuvered the hell out of that airplane for the next forty-five minutes as they (Jap fighters) came in one after the other,” Jay Zeamer recalled.

Lieutenant Britton tried to take control of the floundering B-17 for his badly wounded pilot. Zeamer refused to give up, convinced that the fate of his crew depended upon his own abilities and experience. Unlike a standard bombing mission where, if you were shot down after reaching target, one still had the satisfaction of mission accomplishment, unless Old 666 got back to New Guinea with its film intact the whole ordeal would have been for naught.

“He (Zeamer) was just going at it with a vengeance,” recalled Britton. “I don’t know where he got the strength!”

By 0845 the American bomber was over open seas and the enemy fighters, low on ammunition and fuel, were forced to turn back to Bougainville. Only then did Sergeant Able leave the ball turret. He hobbled up to the cockpit on his two wounded legs. There he found his Zeamer covered in blood and there was a fire in the oxygen system behind his seat. He shouted for Lieutenant Johnston to come help him, and together the two wounded crewmen beat out the flames.

Sergeant Pugh left his position at the tail gun to check on Lieutenant Sarnosk in the ruptured nose of the aircraft. He found the Eager Beaver’s bombardier still slumped where he had fought valiantly throughout the fray, poised over his gun with his finger on the trigger.

Pudgy Pugh lifted him up and pulled him away from the jagged edges of the ruined battle station. Gently he cradled the body of his friend while Old 666 continued its desperate flight home. Halfway there, his head resting in the young gunner’s lap, Joseph Raymond Sarnoski died.

Lieutenant Britton and Sergeant Kendrick turned their attention to their wounded pilot, cutting away clothing to find his multiple wounds and try and stop the bleeding. Throughout the long flight home the indomitable airman passed in and out of consciousness, but he refused to give up control of his airplane. “I don’t move until the mission is ended,” Zeamer announced.

His determination aside, both of Jay’s legs were paralyzed, both arms were useless, and he was literally controlling Old 666 by his finger tips. Sergeant Vaughn managed to give him a shot of morphine to ease the pain while Sergeant Able took a position in the co-pilot’s seat to fly the bomber home. (Lieutenant Britton, the co-pilot, was occupied with tending the wounded and relaying messages from the radio room to the cockpit.)

“Captain Zeamer, although severely wounded and losing blood continuously, remained conscious throughout the trip,” wrote the 19-year old gunner. “Although in great pain he kept his head and kept command of the ship until we landed. I have never seen a man with so much ‘guts’.”

Shortly before noon Sergeant Able saw the northern shoreline of New Guinea in the distance and returned the co-pilot’s position to Lieutenant Britton.

Fighting waves of unconsciousness brought on by the loss of blood, Captain Zeamer still directed the return and subsequent landing. Fearful that Old 666 was so badly shot up that it wouldn’t clear the Owen Stanley Range, he ordered Britton to land at Dobadura.

Without hydraulics or brakes the co-pilot managed to bring the ship home, taxiing to a stop at 1215. In only eight-and-a-quarter hours several lives had been changed, one life had been lost–and just perhaps, due to the incredible determination of one B-17 crew, thousands of Marines might be saved.

The rescue crew that welcomed Old 666 to Dobadura that day were astounded by what they saw. The fortress bore the marks of 187 bullet holes, andgaping wounds from five 20mm cannon.

While the wounded were helped to the ground and loaded in ambulances, the semi-conscious Zeamer overheard one man remark: “Get the pilot last. He’s dead!”

Reports of Captain Zeamer’s death, including a death notification to his parents back in the United States, were premature. More than 120 pieces of ragged steel were picked from his body and three days of blood transfusions were required to keep him alive.

During the ordeal the intrepid pilot had lost 50% of his blood volume and by all best estimates, he should not have survived.

His leg was shredded and even after Jay’s prospects for survival improved, time it was feared that his leg would have to be amputated. Only the fact that he had lost so much blood that the surgeons believed he would not survive the amputation prevented that drastic measure.

Jay’s determination to live was perhaps the only thing more incredible that what he had accomplished in the cockpit of Old 666 on a fateful mission over the Buka Passage.

In his own memoirs, Fifth Air Force Commander General George Kenney wrote: “Jay Zeamer and his crew performed a mission that still stands out in my mind as an epic of courage unequaled in the annals of air warfare.”

Raymond Sarnoski died in the arms of Pudgy Pugh on the flight home. His personal determination to remain at his guns during the most critical moments of the mission had made the difference, but he paid for it with his life.

Two days after the mission a memorial service was held to remember Lieutenant Raymond Sarnoski, and the bombardier was buried on a knoll near the New Guinea airstrip.

Sergeants Able andVaughn obtained permission to leave the hospital beds where their wounds were being treated in order to attend the ceremony. The four uninjured members of the crew were also present, as were scores of other airmen.

Lieutenant Johnston’s head woundwas second in severity only to the wounds suffered by Jay Zeamer. Both men were not only confined to hospitals for major medical attention and neither man was even told that Joe Sarnoski had died for several days.

Five months later, while still undergoing treatment at Winter General Hospital in Topeka, Kansas, Jay wrote a letter to Joe’s sister Agnes stating:

“I watched the zero that hit both Joe and myself explode in the air when Joe’s tracers hit it,” he wrote. “A twin engine fighter followed it in but Joe promptly shot him down too. I could see into the nose compartment through holes which had been shot in my instrument panel. Joe was trying to pull himself back up to his guns then but couldn’t make it anymore. I knew then that he had also been hit but I didn’t know how badly.”

“When we landed I was temporarily blind (from loss of blood) and nobody would tell me that Joe had died until two weeks later when I was evacuated from New Guinea.”

While scores of airmen rushed to give blood to keep Jay Zeamer alive during the first critical 72 hours after the mapping mission, Colonel Meriam C. Cooper was reviewing accounts of the mission.

As chief of staff to Major General Ennis C. Whitehead, Colonel Cooper had witnessed many reports of great bravery and determination in two world wars. (As a young officer in World War I, in fact, it had been Cooper that had recommended Frank Luke for the Medal of Honor.) After reading the reports of the mission over Buka Colonel Cooper wrote:

“I consider Captain Zeamer’s feat above and beyond the call of duty, comparable to that of Lieutenant Luke, who stands with Captain (Eddie) Rickenbacker as one of the leading flying officers of exceptional courage and daring during the last World War.”

General Kenney promptly endorsed Zeamer’s recommendation for his country’s highest honor. It was presented in a special Pentagon ceremony by General Henry Hap Arnold on January 6, 1944.

Thirty days before that presentation the nomination for Lieutenant Sarnoski’s Medal of Honor was also approved.

It was presented to his widow Marie at Richland Army Air Force Base on June 7, 1944.

Marie subsequently gave the Medal to Joe’s parents, who in turn granted possession to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

These presentations marked the first time since World War I and the fateful mission of Lieutenants Harold Goettler and Erwin Bleckley to find The Lost Battalion, that the Medal of Honor was presented to two men from the same airplane.

The other seven courageous Eager Beavers were not forgotten in the efforts to recognize the valor of the crew that had accomplished the mission no one else wanted. All seven were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor.

It made the nine men who flew the in Old 666 on that June 16, 1943, mission over Bougainville, perhaps the most highly decorated aircrew in the history of military aviation. (When these nine awards, along with five Purple Hearts are added to the multiple high awards previously awarded members of the Eager Beavers, there is no doubt no other aircraft has ever boasted a more-decorated crew.)

On June 30, just two weeks after the photo/mapping mission of Bougainville, Operation Cartwheel was launched with MacArthur’s infantry landing 60 miles south of Lae and Admiral Halsey’s 43rd Infantry (US Army) landing on New Georgia in the first leg of the march to Bougainville.

Six months later US Marines stormed ashore on Bougainville Island. Their landing point was at Empress Augusta Bay, the place where Zeamer and crew had ignored enemy fire until the needed photographs of the landing site could be taken.

At the time of this writing (November, 2003), Lieutenant Colonel Jay Zeamer, USAAF (Retired) was the only Army Air Force recipient of the Medal of Honor still living. He passed away on March 21, 2007.****

I am going to close with two tribute videos. The first is a salute to the designers and builders of the B-17, which was legendary for the amount of punishment it could take and still gets its crew home. This is a one minute slow motion gun camera film of an experienced German pilot expertly raking a B-17 from wing tip to wing tip with 20mm cannon and machine gun fire.

The rear and belly turret gunners do not seem to have faired well, but the plane reacts like nothing is going on. The fighter almost rams the plane, seemingly out of frustration that he has not brought it down after shredding it to pieces.

The second is a tribute from those of us here at VT for all the airmen who did not come home. Life expectency was 14 missions. Their tour was 35…so they had to beat the odds about 250%….Jim Dean, VT.

B-17 shot to pieces by German fighter

For those who did not come home

*** Mr. Jim Rembisz is a high school teacher in Joe Sarnoski’s home state of Pennsylvania. He uses the story of Jay Zeamer and Joe Sarnoski to teach history and patriotism to his students. His research has uncovered much untold information about these two men, including personal letters before, during and after their fateful mission. During a visit to Japan he obtained the official combat record of Yoshio Ooki’s 251st Kokutai squadron and had it translated from Japanese. His records, copies of letters, subsequent correspondence with Jay Zeamer, and other important materials were instrumental in preparing this story.

Jim W. Dean is VT Editor Emeritus. He was an active editor on VT from 2010-2022. He was involved in operations, development, and writing, plus an active schedule of TV and radio interviews. He now writes and posts periodically for VT.

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy

Comments are closed.