A Used Book Review, and The WW II Veteran, Milt Felsen

by Erica P. Wissinger

Excerpt: “We continued on toward Brunete, but not very far. The enemy had set up a line of resistance. The machine gun company spread out behind a low wall and began to return the enemy fire. Fighting became intense. Both Dave and our water cooled Mother Bloor ran dry and overheated. The gun showed signs of jamming.

“We need water,” said Dave. “Where in hell can we get some water?”

“There’s only one way,” I answered. “We must pee in it.” We did, but it wasn’t nearly enough. We shouted for the soldiers lying near us to crawl over.

“You must pee in Mother Bloor, I said. “She needs you desperately.” The first soldier made his contribution. The next one refused.

“I can’t,” he said, “it’s sacrilegious. My father reveres Mother Bloor. He would kill me if he heard.”

“About two hundred yards from here are several hundred Moors very anxious to do that ahead of your father,” said Dave, “Pee, dammit!”

Very suddenly, as we lay as flat as we could while raking the opposing line with machine gun fire and receiving it too, we heard behind us wild shouting and the thunderous gallop of many horses on the dead run. In utter astonishment, we ducked for our lives as Spanish horsemen, wearing broad-brimmed hats bedecked with the flamboyant colors of the Republic and brandishing sabers, leaped high over our heads and raced crazily forward into the teeth of the enemy’s chattering machine guns as though engaged in some timeless, existential steeplechase.

“What in the goddamn hell is that,” I said.

“If I am not mistaken,” said Dave, “THAT is the Spanish Cavalry famed in song and story.”

“They’ll be massacred,” I worried. “I can’t watch.”

But by a miracle, they weren’t. The Fascists were equally astounded. Before they could react, the cavalry began to cut them up and they broke and ran. The offensive continued. By nightfall, eight or nine towns had been taken. For a few days it went better than planned, and then we came to Mosquito Ridge.”

There are probably a million people out there who have read a biography of a departed warrior from the past ~ pick a century, any century ~ and wished they could have met them or patted them heartily on the shoulder for their force of character. With this flock of wise old owls who have studied military history far beyond the few books I have read, no doubt this idea will intrigue like a vole scurrying across an open meadow at night. Let me know in the comments whom you wish you could have met, or the living legends you met in person.

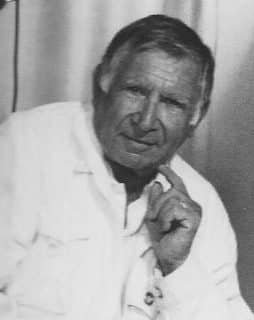

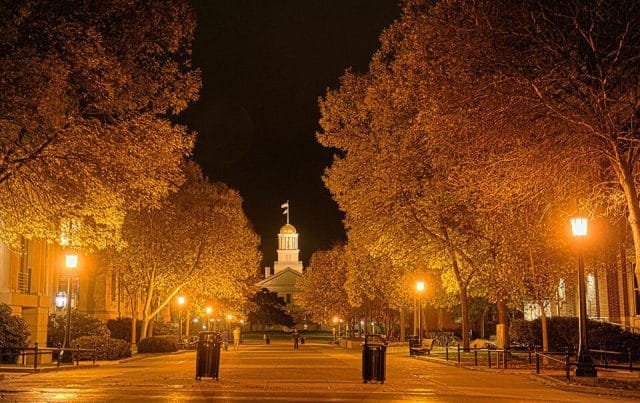

One such warrior was Milt Felsen, who wrote The Anti-Warrior, a Memoir. Milt was born in 1912 in New York City, grew up on the streets of New York, and then grew up some more in the countryside outside New York where he learned the difference between such things as cows and bulls, and ended up as a student at the University of Iowa, where he escaped stern punishment for his political activism by his wit and humor. Here is an excerpt from his college years.

“In September of 1936, we decided to hold an anti war rally. We took copies [of the announcement posters] to be routinely stamped, ‘approved by the President’s office’ before putting them up around campus. The president’s office was artistically and politically shocked to its shoelaces, and refused to apply its little stamp.

“I called a meeting of the American Student Union (ASU) executive committee, and we decided to defy the ban and put up the posters late that night. The Iowa campus is graced by some of the oldest, leafiest and most beautiful trees to be found on the green earth, and my brother Hank and I and Merle were well up in one of them, when a powerful beam of light was aimed at us.

“Standing below was the entire Iowa City police force of eight men, the sheriff and the head of the American Legion.

“‘Come down out of there!’ the shout came from the sheriff. He was weaving a bit. He and the American Legion had been drinking, quite heavily.

“‘Sorry,’ I said, ‘we’re busy. Got some work to do up here.’

“‘You’re under arrest, goddammit. Come down!’

“‘What’s the charge?’ I demanded. I prided myself on my knowledge of constitutional rights.

“There was a short, intense conference down below, then agreement. ‘For COMMITTING COMMUNISM!’ the sheriff shouted, waving his long-barreled pistol.

“‘Yeah,’ added the American Legion, inspired, ‘AT NIGHT.’ I consulted with Hank and Merle.

“‘It sounds to me,’ I said, ‘like a real conceptual breakthrough. I think it would be best to go down.’

“We were thrown into the police cars and taken to the station house. We sat, while one of the cops twirled the barrel of his pistol menacingly, pointing it at us just as he had seen it done in the movies. I demanded our right to make a phone call. The chief came in.

“‘And just whom is it you wish to call?’ he asked sardonically.

“‘Mayor Tom Martin,’ I said. Merle and I had headed up a student political action committee that had helped Martin win. Some of the air went visibly out of the chief’s balloon. Martin came on the phone, half asleep. It was after 1 a.m. I explained.

“‘Let me talk to the dumb bastard,’ said the mayor.

“We sat and enjoyed the chief’s discomfiture and listened to his ‘Yes, Mr. Mayor. OK, Tom, right away, Tom.’

“Finally he hung up, turned to us and snapped, ‘All right, you can go home now.’

“‘We need our posters,’ said Merle.

“‘No way,’ said the chief.

“‘Gimme the phone again,’ I said.

“The chief glared, but he gave up the posters. We still hadn’t won, though. Not quite yet. There was a vagrancy law in Iowa — after 11 P.M. it was illegal to stop moving. Wherever we went, the cops followed us, so we finally went home.

“Some of the most politically active ASU members were in the sororities, and we called around and explained the emergency. A dozen young women, among them the Hickenlooper sisters, eagerly accepted such an exciting and challenging assignment. By 4 A.M., posters had sprouted like night blooming flowers all over the campus.

“Bourke B. Hickenlooper, owning a name that sounded like it belonged in the first line of an off color limerick, was president of the Iowa state senate and would soon become one of the most atrocious U.S. senators. He made a phone call to the university’s President Gilmore. According to the Hickenlooper sisters, who were mightily amused, the conversation went something like this.

“Hickenlooper: ‘Gilmore? I hear there’s a whole bunch of goddamn Reds running your goddamn school down there. If you don’t see to it that my daughters stop being molested by Commie New York Jews, you can kiss any of those appropriations you asked for goodbye. You’ve seen your last goddamn state dollar. Understand?’ Gilmore: ‘Yes, Sir. I understand.’

“Shortly thereafter there was a meeting in President Gilmore’s office. He hinted that he had had a message from Senator Hickenlooper, chairman of the committee that appropriated, or withheld, funds for land grant institutions, of which the university was one.

“Clearly uncomfortable, he addressed his remarks to me. ‘If this university has any validity, it lies in the encouragement of free inquiry, free expresson, the pursuit of truth in an open marketplace of ideas. I believe your group has expressed similar objectives.’ He paused. ‘The freedom of students is not to be inhibited, but the university must deal with the real world, with practical problems.’ He went on to talk about appropriations and budgets and to ask of what use were ideals if they couldn’t keep the doors open.

“I smiled to myself, thinking, He who pays the piper calls the tune. All of us on the committee had gotten the point, and I sensed it was time to make a deal. We held a strong hand.

“‘OK, President Gilmore, we have no wish to embarrass the school. We will have a talk with the Hickenlooper sisters. We cannot, of course, censure them, but we will try to get their cooperation. We expect in return that there will be no more nonsense about stamps on our posted material. One more thing. We are planning a public debate entitled ‘What is Americanism?’ We would like you to be one of the participants.’

“President Gilmore knew when to fold the cards. ‘I predict for you,’ he remarked to me, ‘a brilliant future in the field of extortion.’

“In 1936 there were thirteen thousand students at the U of I, the vast majority of whom concentrated their normally brief span of attention on their chances for material advancement, football, and casual sex. Yet almost 800 of them attended the anti-war rally we had undergone such trauma to advertise, and almost all signed a form of the Oxford Pledge, in essence, ‘I refuse to bear arms in any war.’ (The train of history takes many turns. Only five years later, they would forget they had ever made such a pledge.)”

After participating in the Spanish Civil War as an ambulance driver in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and meeting Ernest Hemingway, Milt returns to America and his surveillance files listed him with the dreaded, “P.A.”, stamped in big red serial killer letters on his dossier, which means Premature AntiFascist.

This is how the US government flagged union organizers and/or communist leaning citizens who opposed fascism, before the US announced its approval for opposing Fascism.

The US checkered flag to oppose fascism was only waved when America joined the war against Germany in 1941, but if, in the 1930s, you opposed fascism a millisecond before the checkered flag dropped, you were stigmatized and could not get a government job.

A review of this book, The AntiWarrior on Goodreads by Tbfrank speaks about the ambivalence by nations on the fascist question:

“From [Felsen’s] point of view, the [Spanish Civil] war demonstrated the support of the world’s democracies for Fascism as the natural opponent to Communism. While Russia supported the Loyalists, the Soviet Union was criticized for supplying weapons rather than troops (identified elsewhere as its customary practice – expend others rather than your own), then blamed as agitators for creating divisions within the Loyalist groups.

“(True or not, Alan Furst adopted some of these ideas in two of his pre-WWII novels touching on the Spanish Civil War.) Oh, and by the way, Felsen met and pal’d around with Hemingway.

“Between one war and the next, Felsen becomes integrated in the economic machine he often disparages. He comes to understand the nature of power in America, who has it, and who does not, as dictated by economics.”

As of May 2022, there are a few copies of Felsen’s book for purchase on the Internet. There are bloody and gutsy chapters describing the two war fronts that Milt served in. Below, the prisoners’ story is for someone out there in the multiverse who needs to hear it, to save their life. I don’t know who, but I feel them and I hope for their survival.

Wild Bill Donovan snapped up some of the Lincoln Brigade, including Milt, to train them for his newly formed OSS, and sent them to Algiers in 1942.

They were wounded and captured; and before Felsen and others were sent to the German prison camp, Stalag 17, they were prisoners in Italy, and were planning a prison break, but of course their clothes and shoes had been confiscated.

“‘First thing we’ll need,’ said Jim, ‘is our clothes and shoes.’ We decided we had better meet with the general. Gordon Forrester was the very model of an English major general – tall and slender, with a gray moustache and a voice so upper class it was virtually impossible to understand a word he said. For the six months the prisoners had been there, he had sulked about the ignominy of his capture, and had rarely been seen outside his private room.” A meeting with the general was arranged.

“Ever since capture, I had tried and failed to understand the European military tradition that mandated prisoners to behave as if they were not prisoners. Foot soldiers had to salute and obey corporals, corporals obeyed sergeants, sergeants obeyed lieutenants, and so on up the line. Their captors, in turn, gave instructions for what they wanted done only to the highest ranking prisoner, from whom orders went back down the line and were carried out without resistance, since soldiers are not in the habit of defying their own superiors.

“As a system for controlling thousands of men who might otherwise have considered it their duty to continue to struggle in every way they could against the enemy, it was just about perfect. But it had the smell of collaboration about it, like a pact among nations to protect each other’s entrenched bureaucratic establishments above all. War is so educational, I mused; they should give a course in some of these things to high school seniors just before they graduate.

“The surprise was that when we finally got to him, the general was decent and helpful. Jim became the spokesman, and he came directly to the point.

“‘Sir,’ he said, ‘the scoop is that Italy has had about enough of this bloody war and may soon quit. But according to the information that you have given us yourself, most of Italy, including this area, is still held by the Germans… The minute Italy goes, we want out of here. We have good evidence the population is anti-German, and would likely help us.’

“The general nodded. ‘Quite right,’ he said, ‘it is the unquestionable duty of every prisoner regardless of rank to escape and rejoin his unit. I appreciate knowing your plans. But surely, there must be another reason for coming to me?’

“‘Yes,’ said Jim, ‘we have no clothes, no shoes. And we have no idea where they are stored. We thought you might know or be able to find out.’

“‘Right,’ said Forrester, ‘I do know. But you will want more than that. I will instruct one of the officers to draw a complete schematic of the interior, indicating stairways, exits, and so forth.’ He hesitated. ‘Report to me please, before you act.’

“‘Yes, Sir.’ We saluted and left, feeling pretty good. It was September of 1943. For two weeks, there had been only one topic of conversation. When would surrender come? Should those who intended to make an escape leave singly, in pairs, or in groups? We decided to go in pairs and fan out in different directions. Then it came, late one afternoon. Every radio station in the country announced that as of the next morning, Italy would be out of the war.

“Jim and I and the rest of the escape committee called a meeting of the entire group. At 7:30 P.M. the meeting was drawing to a close, when General Forrester’s aide de camp made his way to the front of the room.

“‘Hold it!’ he ordered. ‘We have new information, and General Forrester has issued new instructions.’ We waited.

“‘Twenty minutes ago a BBC broadcast carried an official communiqué from the Allied High Command. The gist of it is that all prisoners in all locations are to remain exactly where they are. Special units of the Allied forces are being dispatched immediately to release all captives.’ The aide de camp finished, looked around at the stunned faces, and added, ‘Orders are to get your asses back in bed.’ He left.”

The prisoners decided to go get their clothes and break out anyway. When they reached the clothing storeroom, there was a guard in front of the door holding an Italian rifle. The guard was an English corporal, posted there by Forrester. They argued with the guard, and then General Forrester appeared.

“Everyone, of course, saluted. ‘Gentlemen,’ Forrester said, ‘we have no choice. The broadcast was very clear. The armies know exactly where we are, but if the prisoners were to leave, they would be in danger of being shot by the Germans, or by the Italians. It would also mean a wasteful, time consuming effort trying to round up such personnel wandering around at random.’

“He spoke to an angry, unconvinced audience. ‘Sir, how do we know when they will come to free us?’ asked someone. ‘Sir, we want to take that chance. We are supposed to take it. As far as being shot at, that’s part of it; that’s how we got here.’

“The talk continued, but we all knew it wouldn’t matter. Forrester had made a decision as natural to him as breathing: FOLLOW ORDERS.

“Morning came. Precisely at 11:30 A.M. they came, a dun-colored motorcycle with a plump Gestapo officer in the sidecar, followed by a half-track troop carrier spilling tough-looking German soldiers.

“Trucks had come, and we were boosted and packed aboard. It had taken less than half an hour to roust us all out.

“The BBC broadcast had been a fake. General Forrester had been following the orders not of the Allies, but of the North Italian Sector of the German High Command. He would certainly face a court martial when he got back to Britain. As it happened, he didn’t wait. He committed suicide in Offiziers Lager XII near Breslau, in Germany. It had been a clever ruse by the Germans, and not only Forrester had been fooled.”

I searched for Felsen’s obituary. He died in April 2005, in the same month as Pope John Paul II, and my old friend, The Reverend Robert D. It would seem that a remarkable delegation of human souls marched on to their third estate in April 2005.

Milt Felsen was a producer on the movies, Saturday Night Fever (1977) with John Travolta; and The Bell Jar (1979) with Julie Harris; and the documentary TV series, The Directors (1997-2008). He worked in the independent movie industry; and lived happily with his wife in Florida until he passed on, and she eulogized him in a loving comment. Thank you, Milt, wherever you are, for leaving 245 pages of written words for us about the nature of war and life.

I’m pleased to see that a video interview with Milt Felsen is featured among the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Film Archives, Oral History Collection, at the Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives of New York University at,

NYU Digitaltamiment Albafilms Item 4122 Milt Felsen

“Too many will not get across [the Ebro River],” said Hemingway,

“Too many will die because a superior cause

is not a match for superior fire power.”

Hitler’s Rehearsal for World War II:

“I’d known Milt Felsen for years without knowing he was a veteran of The Abraham Lincoln Brigade. . . The Spanish Civil War is not taught in American schools even though it was Hitler’s rehearsal for WWII.” Paul Leaf, book reviewer.

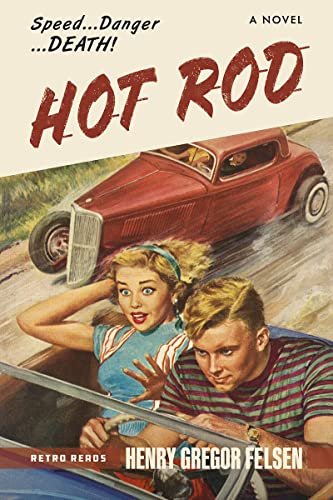

By the way, up in the tree with Milt was his younger brother, Hank Felsen, who became the well published author of the Hot Rod cars series, which is still available on Amazon.

After struggling financially during the Depression, Hank Felsen sold nine books and hundreds of stories in his first eighteen months of full-time freelance writing in the early 1940s. He served in the Marine Corps, and edited the Corps’ magazine Leatherneck and also wrote magazine articles while stationed in the Pacific.

His best-selling book was Hot Rod, one of a rodding series that also included Street Rod and Crash Club and sold about eight million copies in all. He wrote about 60 books.

He is also credited with one screenplay, for the 1968 film Fever Heat, based on his novel of the same name which had been published under the pen name of Angus Vicker. [Ref. Wikipedia]

Eulogy for Hank, from Jalopy Journal: “Way back when I knew Hank Felsen (aka Henry Gregor Felsen). He was a mentor… In the mid-1960’s I was a journalism student at Drake University in Des Moines and took Hank’s creative writing class. For a year or two he allowed me into his life, urging me to pursue the life of a novelist. I went the more ordinary route, going to work for the “Des Moines Register” which led to a 40-year career in newspaper journalism… I have many fond memories of [Hank]. He was most helpful to me in my formative years. I remember Hank had at least a son (he wrote a book about “Letters to a son in Vietnam” or something like that) and a daughter… You had a wonderful father.”

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy

Hannibal Barca, Leonidas, Võ Nguyên Giáp, Manstei, Rommel, Emílio Guevara, Fidel castro, Gergy Zhukov

The superiority of Rommel and the Wehrmacht will never be seen again. Electronics has since replaced military instincts to the point that war has become a huge computer game.

The highest decorated military in the entire portuguese militay History. A man with more than 1850 combat exits and the only man from the war with the title of hero.

Comments are closed.