KIEV, UKRAINE — On March 7, Anatoly Shariy, a Ukrainian opposition figure and one of the country’s most popular journalists, received an email from Igor, an old acquaintance with whom he had not communicated for years (Igor is an alias used to protect his identity).

“Please help me find a place to live, suggest an apartment or an agent. I’m ready to do any work for you, whatever you say,” the email read.

“I realized that he was in the hands of the SBU,” Shariy told me, using the acronym for Ukraine’s domestic intelligence agency, notorious for its persecution of anyone accused of sympathy for Russia. “I understood whom I was talking to and did not particularly answer anything.”

Shariy suspected that the SBU wanted Igor to surveil him for an assassination attempt.

Four days later, Shariy received an email from a different address. This time, it was Igor, confirming Shariy’s suspicion that the first email had been written by an SBU agent. Igor explained that he had been interrogated and tortured for his ties to Russia.

“I realized that the SBU officers were preparing an assassination attempt on Anatoly and decided to agree to warn him that his life was in danger,” he told me in a phone call.

Shariy has lived in exile since 2012, having fled during the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych and received political asylum in the EU. His opposition to the 2014 Maidan coup d’etat grew his profile and made him a target of Petro Poroshenko, who came to power in its wake. The neo-Nazi movements he had exposed in prior years had gained serious political power and intensified their aggression against him.

In 2015, Lithuanian media branded Shariy as a “favorite friend of Putin,” and the Lithuanian government soon revoked his asylum. Shariy, meanwhile, had sought protection elsewhere and relocated to Spain, where he has continued to grow into one of the most popular critics of President Volodymyr Zelensky.

However, his predicament has hardly improved. In 2019, Alexander Zoloytkhin, a former soldier of the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion, published the address and photos of the house where Shariy, his wife Olga Shariy and young child live, as well as photos of Olga’s car. Ukrainian neo-Nazis demonstrated outside his house and he received numerous death threats.

Today, he is a top target of the Kiev government, neo-Nazi paramilitaries, and the SBU.

Shariy began his career in journalism in 2005, first writing for women’s magazines, and then conducting investigations into Ukrainian oligarchs, organized crime, and neo-Nazi networks.

He became a well-known critic of the 2014 U.S.-orchestrated Maidan coup d’etat, using his YouTube channel video blog to amass an enormous online following. Today, he has nearly 3 million subscribers on YouTube, 340,000 on Facebook, and 268,000 on Twitter, becoming one of the country’s most popular journalists despite living outside its borders for a decade.

In 2019, months ahead of the presidential election, Shariy founded a center-right Libertarian political party, naming it after himself: The Party of Shariy. Appealing to young professionals and small and medium business owners, Shariy’s online popularity transformed him into an important player in building a coalition, consistently polling between three and six percent.

Shariy actively supported Zelensky during the campaign, attacking the incumbent Poroshenko. “I thought he [Zelensky] was determined to follow up on his election promises. I helped him to become the president. It’s true me and my team did anything for him to get the post,” Shariy told m

Shariy’s activists were effective in disrupting Poroshenko’s campaign events.

“We were following Poroshenko everywhere we went with his pre-election tour. There were so many people in each city and town organizing themselves in groups and asking Poroshenko hard questions,” Shariy recalled.

In one July 2019 event, Shariy’s supporters trolled Poroshenko’s campaign motto – “Army – YES, Language – YES, Faith – YES” – answering “Shariy” instead of “YES.”

But Zelensky’s carefully-crafted campaign image of a political outsider dedicated to stamping out rampant corruption – copy-pasted from his hit television series, “Servant of the People” – turned out to be a farce.

Zelensky cut deals with oligarchs and stacked his cabinet with the same figures he spent his campaign criticizing. He spurned the coalition-building efforts that typify Ukraine’s multi-party parliamentary democracy, preferring to cut backroom deals for votes. He even sided with his former bitter rival Poroshenko’s own party in Odessa’s 2020 municipal elections despite his famous quote during the pre-election debates when he told Poroshenko, “I AM YOUR VERDICT” – “Я – ваш приговор”.

“When I realized he was not intending to change anything, the corruption was the same or even worse, we changed our mind,” Shariy said.

Following Zelensky’s victory, he proceeded to eliminate state funding for parties that received under 5% of the vote in the elections. Shariy’s party, having received only 2.23%, was among those that were cut off.

Spurned by the new president who he helped get elected, Shariy publicly denounced Zelensky, remarking that he should “curtail their state funding and shove it up their ass.”

Zelensky betrayed his campaign promises of reform and meaningful progress in the Donbass stalemate, leading to a rapid decline in popular support. This left a niche open which was quickly filled by the Party of Shariy. While older voters traditionally supported Viktor Medvedchuk’s “Opposition Platform – For Life”, Shariy’s online presence and style appealed to younger generations.

On the ground, Party of Shariy activists began to protest Zelensky with the same tactics they had wielded in his favor against Poroshenko, appearing at his events and demanding his resignation.

As Shariy gained political capital and was even considered a possible contender for the presidency in a future election, the war of words between him and Zelensky turned into a bitter rivalry.

Zelensky lashed out at Shariy, accusing him of “trying to increase your rating at the expense of my rating, the rating of the president.”

Ukrainian journalist Yuri Tkachev, who was recently arrested by the SBU, commented that Shariy’s party is much stronger than the polls indicate. “It is strange to think that the government would spend so much energy on an insignificant opposition party. All this makes us think that their ratings are higher than they are trying to show us,” he remarked.

Hunting dissidents on a political ‘safari’

Throughout the election, the anti-Poroshenko antics of the Party of Shariy were met with severe violence from the president’s base, which included ultra-nationalists and neo-fascists. Some who dared to ask Poroshenko difficult questions were beaten. In Zaporizhzhya, a man’s car was set on fire and a woman was assaulted by Poroshenko himself.

This violence continued after Zelensky won the election and his rivalry with Zelensky intensified.

At a June 2020 demonstration in which Party of Shariy members demanded an investigation into the politically motivated attacks on their members, neo-Nazi groups attacked using smoke bombs and tear gas, followed by brawls inside the subway. Afterward, these groups announced a political “safari,” offering rewards for attacks on Party of Shariy members. This marked the escalation of violence meted out against the political opposition, especially targeting the Party of Shariy and its supporters.

In one incident, masked men beat a young man in Kharkiv, leaving him severely injured and hospitalized. In Vinnytsia, men from the neo-fascist group Edelweiss beat a party member in broad daylight, breaking his ribs and puncturing a lung. In another incident, a member of the U.S.-trained neo-Nazi Azov Battalion attacked a member inside their party office.

While members of his party were beaten in the streets and inside their offices, Shariy was under threat. On July 8, 2020, he accused Zelensky of ordering his assassination, publishing a confession given to Catalan Police by Zoloytkhin, the man who had published his address the year before.

Zoloytkhin was wanted in Ukraine for numerous serious crimes, including participation in the 2016 kidnapping and beating of journalist Vladislav Bovtruk. Zoloytkhin confessed to police that top figures in the Zelensky government had instructed him to murder Shariy, and Shariy published a video confession from Zoloytkhin.

In February 2021, the SBU charged Shariy with treason, accusing him of “spreading Russian propaganda,” and summoned him to an interrogation by the SBU. After he declined to appear, he was put on the national wanted list.

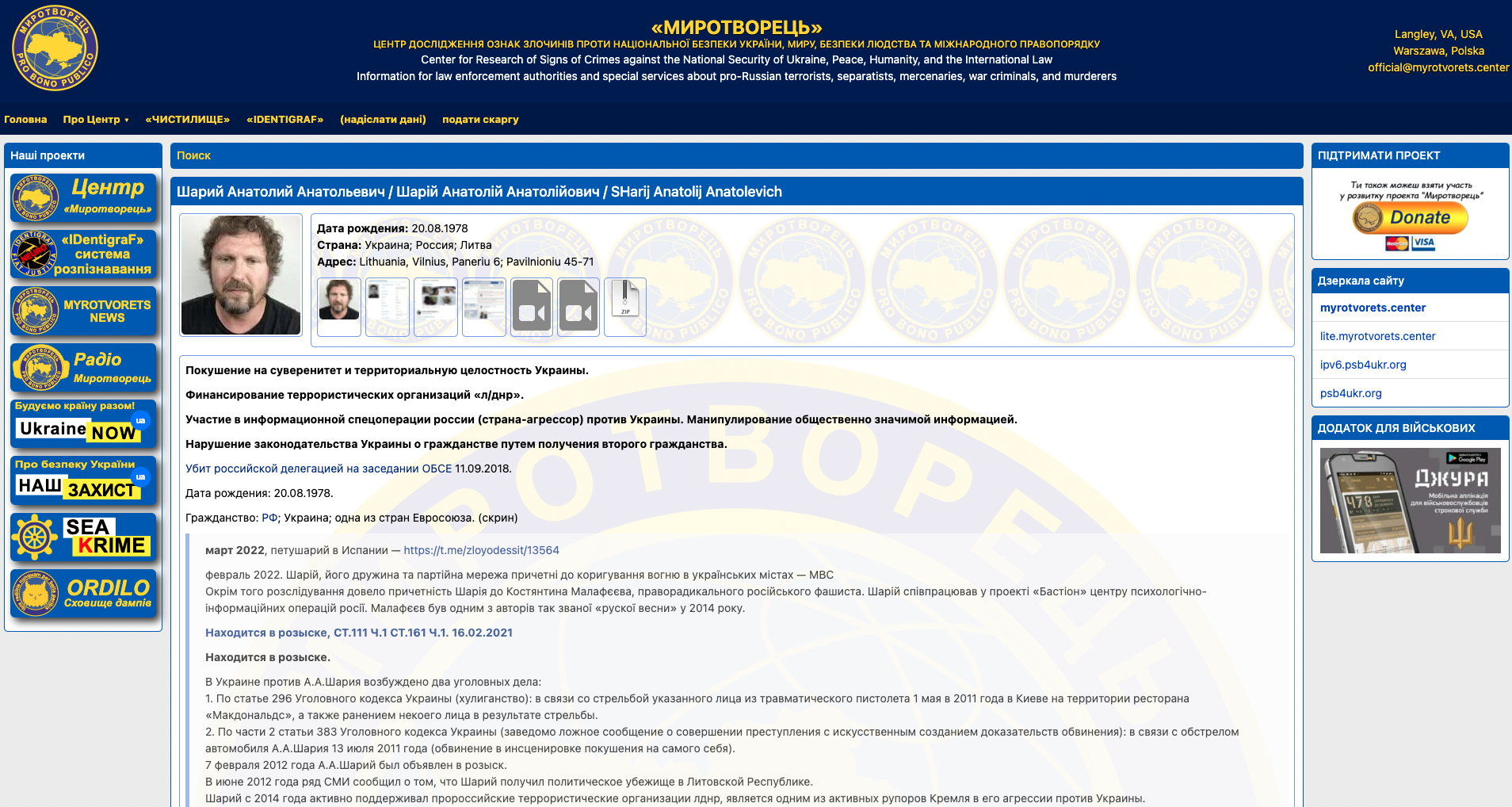

Shariy is blacklisted on Myrotvorets (Peacemaker), an online database of what its owner declared “enemies of the state,” containing personal information and addresses. The blacklist is affiliated with the Ukrainian government and SBU and was founded by Anton Herashchenko, now an advisor to Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. The site accuses Shariy of violating the sovereignty of Ukraine and financing terrorists.

A screenshot shows Shariy on a govt’-linked website that publishes the personal details of enemies of the state

Multiple figures were killed soon after their names were added to the list. On April 15, 2015, Oleh Kalashnikov, a politician from the pro-Russia Party of Regions, the party of ousted president Victor Yanukovych, was shot to death in Kiev.

The next day, Oles Buzina, a prominent journalist and author who advocated for unity among Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia and campaigned to outlaw neo-Nazi organizing, was shot and killed near his apartment.

The culprits were found to be Andrey Medvedko and Denis Polishchuk, neo-Nazis who had served in government and military positions – their confessions were published by Shariy. Yet Buzina’s murderers not only walk free but have received government funding.

The scene of Oles Buzina’s murder. Credit | Ruptly

Zelensky has opened numerous criminal cases against Shariy. He personally enacted sanctions against him, his wife Olga Shariy, and his wife’s mother, Alla Bondarenko. Shariy’s political party was banned in Zelensky’s sweeping March 20 decree that criminalized all opposition parties, accusing them of ties to Russia.

‘An ordinary person confesses at least to the murder of John F. Kennedy’

Prior to the Russian offensive, Shariy appeared often on Russian television, positioning himself as a neutral alternative to Zelensky and his regime of pro-EU neoliberals and neo-fascists. When Russian tanks rumbled across the Ukrainian border, he immediately denounced the invasion, calling the Kremlin foolish for invading a country that he believed would collapse on its own. Nonetheless, the threats against him intensified and Zelensky sought to eliminate Shariy from political life and kill him altogether.

On March 2, Ukrainian intelligence agents arrived at the Kiev home of Igor. The following is an account he gave to MintPress over the phone on April 7.

They took him into custody, handcuffing him and placing a sack over his head, then took him to a sports complex-turned temporary prison, connected to the main SBU headquarters, located in central Kiev between Vladimirskaya, Irininsky, Patorzhinsky, and Malopodvalna streets. Originally constructed as a Trade Union Palace following the Russian revolution, this building became the Bolshevik headquarters of Ukraine. Since 1938, it served as headquarters of the Gestapo during the Nazi occupation, the NKVD of the U.S.SR, and today, as a torture center for Russian prisoners of war and Ukrainians accused of having ties to Russia.

Inside the narrow underground rooms converted to an expansive state security complex, Igor says, SBU agents oversee members of the “Territorial Defense” – ultra-nationalist civilians and criminal elements who the government gave weapons in the streets in the first days of Russia’s offensive – as they beat, torture and even kill their prisoners.

Numerous prominent figures have been kidnapped and tortured by the Territorial Defense and the SBU. Among them are mixed martial arts fighter Maxim Rindkovsky, who was beaten on video and allegedly killed, Denis Kireev, the Ukrainian negotiator who was murdered after being accused of treason, and Volodymyr Struk, the Mayor of Kreminna, who was murdered after being accused of supporting Russia. Even Dmitry Demyanenko, former SBU head of the Kiev region, was shot dead in his car on March 10, accused of sympathy for Russia.

In fact, the SBU is a project of the CIA. Following the 2014 coup, the security service was headed by Valentin Nalyvaichenko, who was recruited by the CIA when he was the Consul General of Ukraine in the United States. The CIA reportedly has an entire floor in the SBU headquarters.

In November 2021, Zelensky appointed Oleksandr Poklad to head the SBU’s counterintelligence. A former lawyer and cop with ties to organized crime, Poklad is nicknamed “The Strangler” – a reference to his favorite method of obtaining testimony from his victims. One article describes another torture method known as ‘The Elephant:’

“A gas mask is put on the victim of torture, and pepper tear gas from a spray can or a poisonous aerosol such as dichlorvos is launched into the gas mask hose. After such torture, an ordinary person confesses at least to the murder of John F. Kennedy.”

Anatoly Shariy, whose political party named the 'Party of Shariy' was just banned by Zelensky, explains that Ukrainian SBU intelligence – led by "The Strangler" – is disappearing, torturing and murdering anyone who has spoken a single word criticizing the regime. Continued below. pic.twitter.com/3z2UoQUbD8

— Dan Cohen (@dancohen3000) March 20, 2022

The United Nations and Amnesty International have both documented SBU torture prisons.

The SBU also closely collaborates with neo-Nazi groups including Right Sector, Azov, and C14, which was contracted by the Ukrainian government to conduct street patrols.

‘A small Guantanamo’

Inside the sports complex-turned temporary torture prison, Igor says the sack over his head was replaced with a blindfold, leaving him only he could only see his legs.

A Ukrainian businessman who had long worked in transportation logistics – including stints in Moscow – a story typical of many Ukrainians, since returning to Kiev, Igor had maintained business ties to Moscow and Crimea, which had joined the Russian Federation after a successful referendum in 2014.

Several family members, including his mother, live in Russia and he regularly visited them until relations between the two countries reached a boiling point in 2021. “With the conflict between Russia and Ukraine and the events of February 24, my mother started to call me very often because she was very afraid of my status,” he told me.

Territorial Defense began to round up anyone suspected of sympathizing with Russia, as well as Ukrainians with cross-border ties, whether family or business.

Inside the makeshift prison, Igor says he identified 25 to 30 distinct voices of imprisoned men, and saw 10 to 12 men in Russian military uniforms, what he believes were prisoners of war. Two of the Russians were severely beaten in order to motivate the others to give on-camera testimony about their hate for Putin and opposition to the war.

Other detainees were religious people known for assembling at military installations to pray for peace and homeless people who had no way to abide by the evening curfew and were swept up by nighttime patrols.

While many of those inside the complex were kept for a couple of hours and released, others were severely beaten. “It was like a small Guantanamo,” Igor recalled.

Igor says that he was interrogated three times, with each session lasting between 15 and 30 minutes. The beatings were carried out by Territorial Defense volunteers while SBU officers instructed them on how to torture and asked him questions.

“They used a lighter to heat up a needle, then put it under my fingernails,” he told me. “The worst was when they put a plastic bag over my head and suffocated me and when they held the muzzle of a Kalashnikov rifle to my head and forced me to answer their questions.

But he says the suffering he endured was minor in comparison to the torture of the Russian prisoners of war, who were beaten with metal pipes while the Ukrainian national anthem played on repeat in the background. “I could hear it because all the torture was done in a nearby room. It was psychologically severe. This was done at night, the sounds of beatings were constant. It was difficult to sleep.”

Listening to conversations of other prisoners, Igor understood that two prisoners from Belarus were beaten to death, identifying one as a man named Sergey.

‘Like a Jew in Nazi Germany’

The existence of the torture prison was corroborated by an account I received from Andrey, a man with citizenship from Russia and a western European country (Andrey is also an alias to protect the identity of the source).

When he was first brought to the prison, Andrey recalls, he witnessed police beating what they told him was a Russian saboteur.

“It’s like mob justice, you know? You just find somebody that roughly fits the description and you take it out on him,” he said.

Tied to a chair, police repeatedly punched the man in the torso, the face, and back of the head as blood poured from his mouth.

“The police weren’t even interested in what he had to say. They would ask a question, he would start speaking slowly and they would hit him in the head,” he said. “They were taking out aggression and fear on him like a punching bag.”

Andrey says police threatened him with the same but he was spared because he held citizenship from a western European country. “I was told that If it wasn’t for my second passport, I’d be killed. I don’t know how much of that was to influence and scare me, or how much it was real,” he said.

During one interrogation, he says he was blindfolded, his hands were taped behind his back, and he was driven to an unknown location. After being taken into a building and up and down flights of stairs, he was thrown to the floor and kicked in the head.

Andrey recalls hearing ultra-nationalistic Ukrainian music in the prison. “Hard bass, electro, rock, rap – it was either to deprive us of sleep or to mask what was going on behind the music.”

Inside the prison, Andrey met Igor, who slept on an adjacent mat. He recalled being uncertain if Igor was an actual prisoner or if he was a plant that would attempt to extract information. In their brief exchanges, Andrey memorized a phone number Igor gave him and contacted him after he was released.

Andrey remains inside Ukrainian borders since his release, worried that the anti-Russia hysteria engulfing Ukraine could lead to his injury, or worse. “I’m like a Jew in Nazi Germany,” he told me.

‘They were very interested in his daily routine’

During Igor’s interrogation, SBU agents found contact information for his uncle, a former Soviet military officer. Believing that his uncle had influence in the Russian military, SBU agents called him to demand he facilitate an exchange of Igor for prisoners of the Snake Island incident.

When SBU agents found videos of Shariy on Igor’s phone, officers from a separate department were called in. From then on, they began to treat him better, removing his handcuffs and giving him larger quantities of food.

Igor’s connections to Shariy were minimal, limited to occasional contact via text message. In 2015, Shariy published a video about an incident in which Igor’s truck cargo was held for ransom by Aidar Battalion militants at a border crossing between Crimea and Ukraine.

Igor subsequently filmed interviews and events for Shariy, though they never met face to face. Nonetheless, SBU agents apparently saw Igor as an opportunity to gather sensitive information about Shariy’s habits.

Hours later, the chief officer came to interrogate him about materials and interviews he had worked on for Shariy. He was then given a blanket and allowed to sleep for two days.

After another interrogation, they instructed him to travel to Spain, where Shariy is taking refuge. “Their main intention was that I would stay at Shariy’s side, assist him in preparing materials, and report to the officers what he is working on, what his status is, what his family is doing, what foods he eats, and where he shops. They were very interested in his daily routine, his movements, and people close to him. They wanted me to be as close as possible to him and at his side as often as possible.”

It was then that Igor realized Shariy’s life was in danger.

“As far as I understood, based on the information that I had to convey, the liquidation of Anatoly Shariy was being prepared, since he poses a danger to the government of Ukraine and criticizes the actions of the SBU, the government, and President Zelensky,” he told me.

The SBU told him an agent stationed in Spain would contact him after his arrival and provide him with further instructions.

Another department of the SBU notified his brother of his arrest, demanding a $1,000 bribe for his release. “For the SBU, this is just a way of making money. They were detaining people and asking for money in exchange,” he said. His brother paid the bribe on March 10, freeing Igor, though Igor’s car was confiscated as collateral. “There are many cases like this. They take civilian cars for the needs of SBU and the Ukrainian army.”

SBU agents had assured Igor that he would be able to pass through Ukrainian borders and enter the European Union, a nearly impossible task for Ukrainian males aged 18 to 60 who are subject to mandatory conscription.

After his release, Igor says he stayed in Kiev for ten days, resting and regaining his health. He then traveled to Transcarpathia, a region in Western Ukraine. Instead of following the orders of the SBU, Igor went to a different western European country. On April 2, he contacted Anatoly Shariy by email, informing him that he believes he is under threat.

“I warned Anatoliy Shariy that there could be an attempt to kill him in Spain.” Shariy understood that Igor’s call represented an extraordinary threat. “I was very tense with questions about the fact that he could be sent to me so that he could find out the places I visit, up to where I eat. The direction of these questions clearly indicates that they have the idea of my physical elimination,” Shariy told me by email.

Now in an EU country, Igor is facing an uncertain future and is unable to return to Ukraine. “I am afraid, not only for my own life but for my relatives and my friends,” he says.

Many on Telegram channels are speculating that the SBU has held Medvedchuk in a prison basement for weeks, and published the photos now to distract from Ukraine’s losses on the battlefield. No way to know, but it can’t be ruled out.

— Dan Cohen (@dancohen3000) April 12, 2022

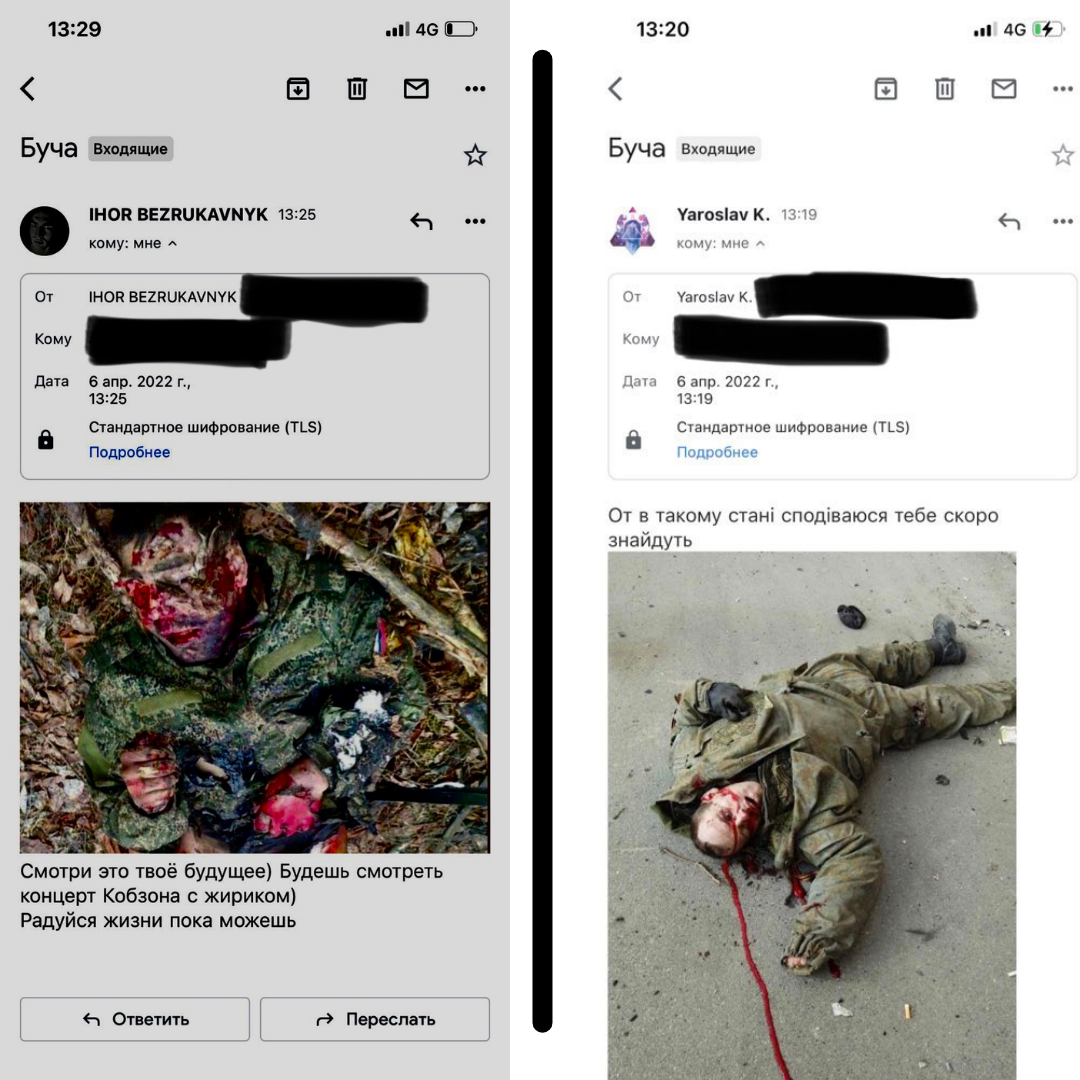

With opposition leader Viktor Medvedchuk, bruised and apparently beaten, in the custody of SBU, the threat against Shariy is clear. He continues to receive death threats against him and his family, sometimes 100 per day, he says.

Left: “Look it’s your future.” Right: “I hope they will find you soon.” Screenshots courtesy of Anatoly Shariy

Feature photo | Image by Antonio Cabrera

Dan Cohen is the Washington DC correspondent for Behind The Headlines. He has produced widely distributed video reports and print dispatches from across Israel-Palestine. He tweets at

Testimony Reveals Zelensky’s Secret Police Plot to ‘Liquidate’ Opposition Figure Anatoly Shariy

ttt

ATTENTION READERS

We See The World From All Sides and Want YOU To Be Fully InformedIn fact, intentional disinformation is a disgraceful scourge in media today. So to assuage any possible errant incorrect information posted herein, we strongly encourage you to seek corroboration from other non-VT sources before forming an educated opinion.

About VT - Policies & Disclosures - Comment Policy